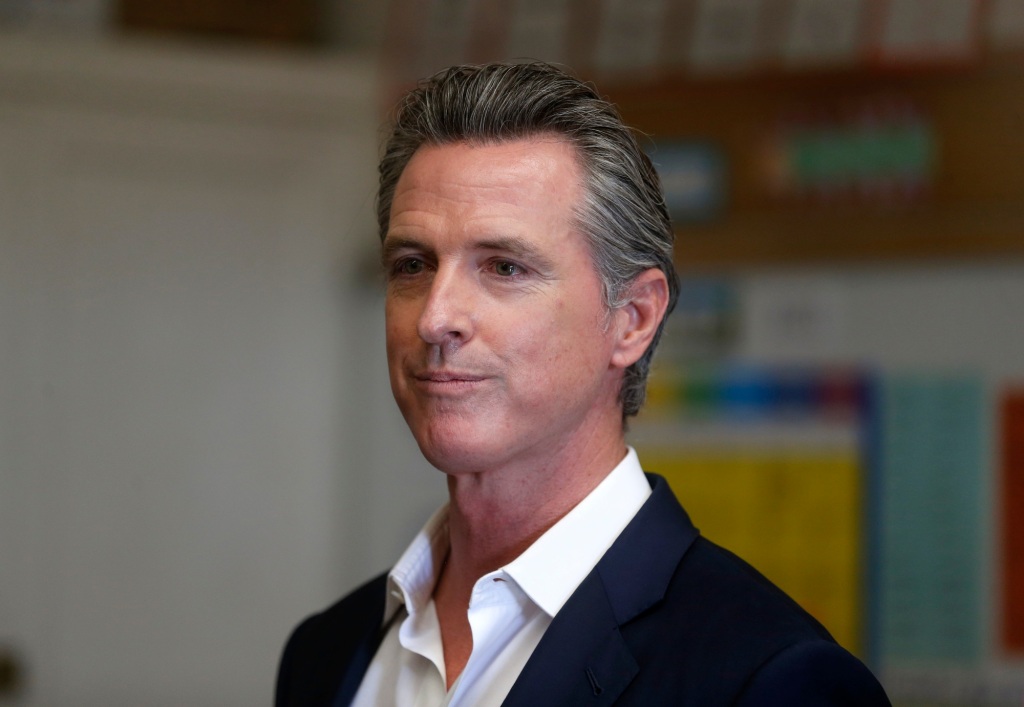

In one of his first actions after surviving an election seeking to oust him from office, Gov. Gavin Newsom on Thursday essentially abolished single-family zoning in California — and green-lighted a series of bills intended to bolster the state’s housing production.

By signing Senate Bill 9 into law, Newsom opened the door for the development of up to four residential units on single-family lots across California. The move follows a growing push by local governments to allow multi-family dwellings in more residential neighborhoods. Berkeley voted to eliminate single-family zoning by Dec. 2022, and San Jose is set to consider the issue next month.

While opponents fear such a sweeping change will destroy the character of residential neighborhoods, supporters hail it as a necessary way to combat the state’s persistent housing crisis and correct city zoning laws that have contributed to racial segregation.

“The housing affordability crisis is undermining the California Dream for families across the state, and threatens our long-term growth and prosperity,” Newsom wrote in a news release. “Making a meaningful impact on this crisis will take bold investments, strong collaboration across sectors and political courage from our leaders and communities to do the right thing and build housing for all.”

The crisis has long been a major concern among Bay Area voters — 89% said homelessness was an extremely serious or very serious problem when polled in January 2020. And 86% said the cost of housing was an extremely serious or very serious problem, according to the poll conducted for this news organization and the Silicon Valley Leadership Group.

Newsom took office with bold promises to attack California’s drastic housing shortage and in his first year landed a budget that included a record $1 billion to fight homelessness and $1.75 billion to build more homes, launched a homelessness task force and put forward a plan that for the first time would fine cities that defied production rules. This year, Newsom has made big commitments to housing Californians, including signing a $12 billion bill to build homeless housing and support services for unhoused people.

Newsom previously had shaken up single-family zoning by signing legislation that allowed more homeowners to build in-law units on their properties. SB 9 takes that further, allowing property owners to build up to two duplexes on what was once a single-family lot.

Slow-growth group Livable California, which has pushed back against SB 9, called it a “radical density experiment” and worried developers would use it to remake neighborhoods without community input.

A property must meet certain criteria under SB 9 before it can be developed into multi-family housing. It must be large enough, for example, and the owner must live there for at least three years before splitting the property. A study by UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation found that the new law likely would add, at most, fewer than 700,000 housing units across California.

Newsom on Thursday also signed SB 10, creating a process that lets local governments streamline new multi-family housing projects of up to 10 units built near transit or in urban areas. That new legislation also simplifies zoning requirements under the California Environmental Quality Act, which developers complain can bog down projects for years.

“SB 10 provides one important approach: making it dramatically easier and faster for cities to zone for more housing,” the bill’s author, Sen. Scott Wiener, D-San Francisco, wrote in a news release. “It shouldn’t take five or 10 years for cities to re-zone, and SB 10 gives cities a powerful new tool to get the job done quickly.”

Newsom also signed SB 8, which extends the Housing Crisis Act of 2019. The act, which speeds up the approval process for housing projects, curtails local governments’ ability to reduce the number of units allowed on a site and limits housing application fee hikes, was set to expire in 2025. Now it will go through 2030.

Finally, Newsom green-lighted AB 1174 — a bill that specifically targets the Vallco housing, office and retail project underway in Cupertino. The city was forced to grant Vallco special approval under a new law that fast-tracks certain residential developments. That approval is good for three years, and Cupertino officials recently said Vallco’s is set to expire this month. AB 1174 clarifies that projects delayed by litigation — as Vallco was — get more time.

“Closing this loophole will protect thousands of new housing units statewide against the whims of local opposition,” Jim Wunderman, president and CEO of the Bay Area Council, wrote in a news release. “Too often, the legal system is abused to block housing that we so desperately need. AB 1174 fulfills the intent of past housing reform legislation to speed more housing construction in California.”