MONTEREY — Presidential candidate Mike Bloomberg said in an interview Friday that his rivals Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders don’t “know what they’re talking about” when they call for breaking up big tech companies like Facebook, Google and Amazon.

Still, he told the Bay Area News Group he was open to more limited antitrust enforcement against the tech giants and voiced support for revising laws that protect them from being legally responsible for the content on their platforms.

“Breaking things up just to be nasty is not an answer,” the former New York City mayor said. “You’ve got to have a good reason and how it would work, and I don’t hear that from anybody, the senator or anybody else.”

“I don’t think they know what they’re talking about,” Bloomberg said of Warren and Sanders.

Warren has championed the idea of chopping up the Silicon Valley titans, arguing that they need to be cut down in order to limit their power and promote competition in the industry and releasing a plan showing how she’d go about the task. Sanders has also voiced support for the proposal, while other presidential contenders have expressed varying levels of interest.

Warren’s campaign declined to respond to Bloomberg. Anna Bahr, a spokeswoman for Sanders, said that “it’s not surprising that a billionaire running for president wants to protect the wealth of his billionaire friends.”

“When Bernie is in the White House, we will break up tech giants that have too much control over our country — and end their corporate greed,” Bahr said.

Bloomberg said he would be open to more targeted antitrust actions against the companies, and acknowledged that they had “too much power.”

“It’s probably true that we shouldn’t have let Facebook buy the last big acquisition they made,” he said.

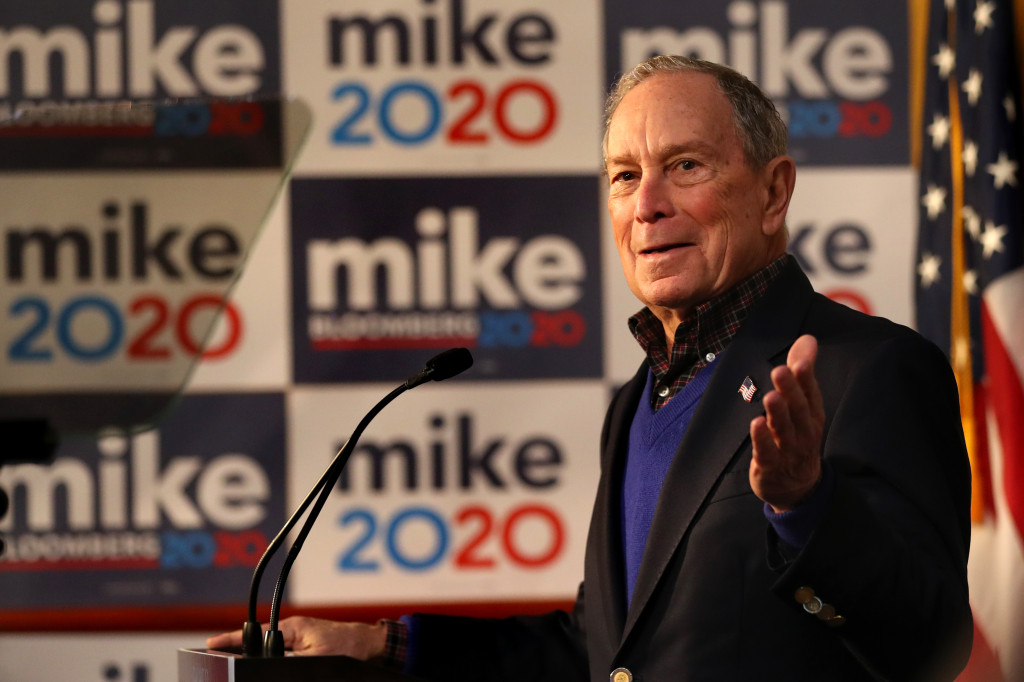

The multi-billionaire discussed his views on tech policy while sitting in a more than 150-year-old adobe building in Monterey, where he gave a speech to about 200 supporters Friday afternoon. Bloomberg’s trip to California this week was his third swing through the state in less than two months as a presidential hopeful.

Wading into another ongoing debate between Silicon Valley and Washington, D.C., Bloomberg said he thought social media companies should face similar legal requirements as newspapers or other media outlets about the information shared on their platforms.

“The rules that apply to your publication, in terms of what your responsibilities are for whatever you distribute to the public, should also apply to them,” Bloomberg said of the tech companies. “And when they say, ‘Well, our system is such that we have a million billion things coming through it, we can’t do it,’ well, change your business model.”

“Society shouldn’t give up the protections that we have from the press’s responsibility just because it helps them make more money,” he said.

It’s a similar argument to that made by politicians calling for the repeal of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, a landmark law that limits tech companies’ liability for content created by their users. Former Vice President Joe Biden said he supported the repeal of the law in an interview published Friday with the New York Times editorial board, making some of the same points as Bloomberg. And the provision has come under heavy criticism from elected officials on both sides of the aisle.

When asked whether he would repeal Section 230, Bloomberg said he wasn’t sure exactly which part of the law he wanted changed. His campaign declined to clarify further.

Bloomberg also said he thought the federal government should pass new data privacy laws or regulations, citing the European Union’s far-reaching provisions giving users control over their data. “I don’t think you have much choice, because if a big chunk — like all of Europe — does one thing, America can’t sit there totally in a vacuum,” he said. “These companies think that because they have information and they can sell it they should have a right to sell it, and society doesn’t have to (allow) that.”

What doesn’t work, he said, is a patchwork of shifting regulations across states and countries that makes it difficult for businesses to operate.

“Tell them the rules — they may bitch a little bit, but they will figure out how to comply with them,” Bloomberg said. “But then it has to stay that way for a while. They just can’t spend all their time changing their business model.”

Bloomberg also defended his decision to push back the deadline for him to disclose documents detailing his vast wealth. Federal Election Commission officials approved his campaign’s request for a second deadline extension Friday, which means he won’t have to file a personal financial disclosure report until Mar. 20 — after voters in more than two dozen states, including California, have already cast their primary ballots.

Bloomberg’s fortune is estimated at $55.5 billion, making him the world’s ninth richest man, according to Forbes. The former mayor has already spent more than $200 million of that on ads promoting his campaign, dominating the airwaves in California and other states.

He said the extra time to file the disclosure was necessary because his team had to review documents from “virtually every country and certainly in every state.”

“We’re trying as hard as we can,” Bloomberg said, pantomiming a huge stack of paper.

He said he would also release his tax returns — which are separate from the financial disclosure — but declined to set a deadline. All of the top Democratic candidates have already released multiple years of their returns, while President Trump has refused to make his public.

“My tax return is very simple: I give all the money away that I possibly can, and then pay taxes on the balance,” Bloomberg said. “It is not that it’s anything complex. I don’t have any tax gimmicks. But there’s a lot of places you file.”