You wouldn’t expect a medical app to get its start as a Snapchat competitor. Neither did video chat startup TapTalk’s founder Onno Faber. But four years ago he was diagnosed with a rare disease called neurofibromatosis type 2 that caused tumors, leading Onno to lose hearing in one ear. He’s amongst the one in 10 people with an uncommon health condition suffering from the lack of data designed to invent treatments for their ails. And he’s now the co-founder of RDMD.

Emerging from stealth today, RDMD aggregates and analyzes medical records and sells the de-identified data to pharmaceutical companies to help them develop medicines. In exchange for access to the data, patients gets their fragmented medical records organized into an app they can use to track their treatment and get second opinions. It’s like Flatiron Health, the Google-backed cancer data startup that just got bought for $2 billion, but for rare diseases.

Now RDMD is announcing it’s raised a $3 million seed round led by Lux Capital and joined by Village Global, Shasta, Garuda, First Round’s Healthcare Coop and a ton of top healthtech angels, including Flatiron investors and board members. The cash will help RDMD expand to build out its product and address more rare diseases.

RDMD founders (from left): Nancy Yu and Onno Faber

“We believe that the traditional way rare disease R&D is done needs to change,” RDMD CEO Nancy Yu tells TechCrunch. The former head of corp dev at 23andMe explains that, “There are over 7,000 rare diseases and growing, yet <5% of them have an FDA-approved therapy . . . it’s a massive problem.”

While data infrastructure supports development of treatments for more common diseases like cancer and diabetes, rare diseases have been ignored because it’s wildly expensive and difficult to collect the high-quality data required to invent new medicines. But “RDMD generates research-grade, regulatory-grade data from patient medical records for use in rare disease drug R&D,” says Yu. The more data it can collect, the more pharma companies can do to help patients.

Trading utility for patient data

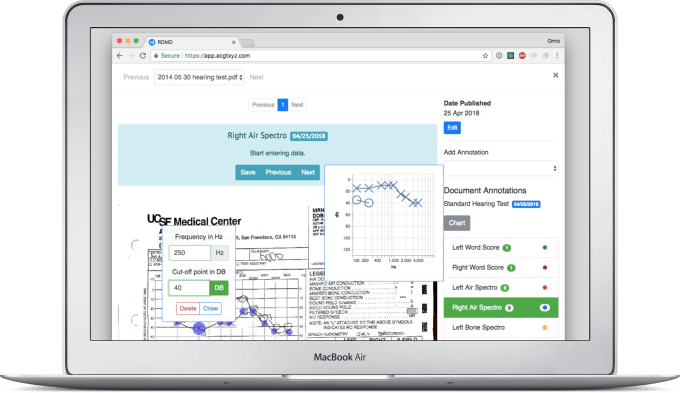

With RDMD’s app, a patient’s medical data that’s strewn across hospitals and health facilities can be compiled, organized and synthesized. Handwritten physicians’ notes and faxes are digitized with optical character recognition, structuring the data for scientific research. RDMD lays out a patients’ records in a disease-specific timeline that summarizes their data that can be kept updated, delivered to specialists for consultations or shared with their family and caregivers.

If users opt in, that data can be anonymized and provided to research organizations, hospitals and pharma companies that pay RDMD, though these patients can delete their accounts at any time. Because it’s straight from the medical records, the data is reliable enough to be regulation-compliant and research-ready. That allows it to accelerate the drug development process that’s both lucrative and life-saving. “It normally takes millions of dollars over several years to gather this type of data in rare diseases,” Yu notes. “For the first time, we have a centralized and consented set of data for use in translational research, in a fraction of the time and cost.”

So far, RDMD has enrolled 150 patients with neurofibromatosis. But the potential to expand to other rare diseases attracted a previous pre-seed round from Village Global and new funding from angels like Clover Health CEO and Flatiron board member Vivek Garipalli, Flatiron investor and GV (Google Ventures) partner Vineeta Agarwala, Twitter CTO Parag Agrawal, former 23andMe president Andy Page and the husband and wife duo of former Instagram VP of product Kevin Weil and 137 Ventures managing director Elizabeth Weil.

“Onno and Nancy realized there’s an opportunity to do in rare diseases what Flatiron has done in oncology — to aggregate clinical data from patients, and to leverage that data in clinical trials and other use cases for biotech and pharma,” says Shasta partner Nikhil Basu Trivedi. RDMD will be competing against pharma contract research organizations that incur high costs for collecting data the startup gets for free from patients in exchange for its product. Luckily, Flatiron’s exit paved the way for industry acceptance of RDMD’s model.

“Onno and Nancy realized there’s an opportunity to do in rare diseases what Flatiron has done in oncology — to aggregate clinical data from patients, and to leverage that data in clinical trials and other use cases for biotech and pharma,” says Shasta partner Nikhil Basu Trivedi. RDMD will be competing against pharma contract research organizations that incur high costs for collecting data the startup gets for free from patients in exchange for its product. Luckily, Flatiron’s exit paved the way for industry acceptance of RDMD’s model.

“The biggest risk for our company is if we lose our focus on providing real, immediate value to rare disease patients and families. Patients are the reason we are all here, and only with their trust can we fundamentally change how rare disease drug research is done,” says Yu. RDMD will have to ensure it can protect the privacy of patients, the security of data and the efficacy of its application to drug development.

Hindering this process is just one more consequence of our fractured medical records. Hopefully if startups like RDMD and Flatiron can demonstrate the massive value created by unifying medical data, it will pressure the healthcare power players to cooperate on a true industry standard.