The Amazon boogie-man has every retailer scrambling for ways to fight back. But the cost and effort to install cameras all over the ceiling or into every shelf could block stores from entering the autonomous shopping era. Caper wants to make eliminating checkout lines as easy as replacing their shopping carts while offering a more familiar experience for customers.

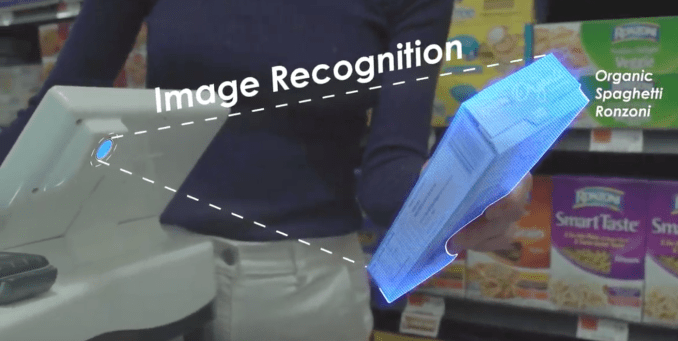

The startup makes a shopping cart with a built-in barcode scanner and credit card swiper, but it’s finalizing the technology to automatically scan items you drop in thanks to three image recognition cameras and a weight sensor. The company claims people already buy 18 percent more per visit after stores are equipped with its carts.

Caper’s cart

Today, Caper is revealing that it’s raised a total of $3 million, including a $2.15 million seed round led by prestigious First Round Capital and joined by food-focused angels like Instacart co-founder Max Mullen, Plated co-founder Nick Taranto, Jet’s Jetblack shopping concierge co-founder Jenny Fleiss and Y Combinator. Hardware Club, FundersClub, Sidekick Ventures, Precursor Ventures, Cogito Ventures, and Redo Ventures also invested. Caper is now in two retailers in the NYC area, though it plans to use the cash to expand to more and develop a smart shopping basket for smaller stores.

“If you walked into a grocery store 100 years ago versus today, nothing has really changed,” says Caper co-founder and CEO Lindon Gao. “It doesn’t make sense that you can order a cab with your phone or go book a hotel with your phone, but you can’t use your phone to make a payment and leave the store. You still have to stand in line.”

Autonomous retail is going to be a race; $50 million-funded Standard Cognition, ex-Pandora CTO Will Glaser’s Grabango and scrappier startups like Zippin and Inokyo are all building ceiling and shelf-based camera systems to help merchants keep up with Amazon Go’s expanding empire of cashierless stores. But Caper’s plug-and-play cart-based system might be able to leapfrog its competitors if it’s easier for shops to set up.

Caper combines image recognition and a weight sensor to identify items without a barcode scan

Inventing the smart cart

“I don’t have an altruistic reason, but I really want to put a dent in the universe and I think retail is severely under-innovated,” Gao candidly remarked. Most founders try to spin a “superhero origin story” about why they’re the right person for the job. For Gao, chasing autonomous retail is just good business. He built his first startup in gaming commerce at age 14. The jewelry company he launched at 19 still operates. He went on to become an investment banker at Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan but “I always felt like I was more of a startup guy.”

Caper was actually a pivot from his previous entry into the space called QueueHop that made cashierless apparel security tags that unlocked when you paid. But during Y Combinator, he discovered how tough it’d be to scale a product that requires a complete rethinking of a merchant’s operations flow. So Gao hoofed it around NYC to talk to 150 merchants and discover what they really wanted. The cart was the answer.

Caper co-founder and CEO Lindon Gao

V1 of Caper’s cart lets people scan their items’ barcodes and pay on the cart with a credit card swipe or Apple/Android Pay tap and their receipt is emailed to them. But each time they scan, the cart is actually taking 120 photos and precisely weighing the items to train Caper’s machine vision algorithms in what Gao likens to how Tesla is inching toward self-driving.

Soon, Caper wants to go entirely scanless, and sections of its two pilot stores already use the technology. The cameras on the cart employ image recognition matched with a weight sensor to identify what you toss in your cart. You shop just like normal but then pay and leave with no line. Caper pulls in a store’s existing security feed to help detect shoplifting, which could be a bigger risk than with ceiling and shelf camera systems, but Gao says it hasn’t been a problem yet. He wouldn’t reveal the price of the carts, but said “they’re not that much more expensive than a standard shopping cart. To outfit a store it should be comparable to the price of implementing traditional self-checkout.” Shops buy the carts outright and pay a technology subscription but get free hardware upgrades. They’ll have to hope Caper stays alive.

“Do you want guacamole with those chips?”

Caper hopes to deliver three big benefits to merchants. First, they’ll be able to repurpose cashier labor to assist customers so they buy more and to keep shelves stocked, though eventually this technology is likely to eliminate a lot of jobs. Second, the ease and affordable cost of transitioning means businesses will be able to recoup their investment and grow revenues as shoppers buy more. And third, Caper wants to share data that its carts collect (on routes through the store, shelves customers hover in front of and more) with its retail partners so they can optimize their layouts.

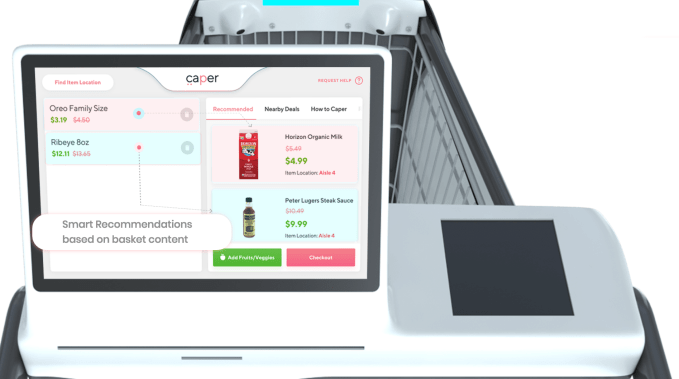

Caper’s screen tracks items you add to the cart and can surface discounts and recommendations

One big advantage over its ceiling and shelf camera competitors is that Caper’s cart can promote deals on nearby or related items. In the future, it plans to add recommendations based on what’s in your cart to help you fill out recipes. “Threw some chips in the cart? Here’s where to find the guacamole that’s on sale.” A smaller hand-held smart basket could broaden Caper’s appeal beyond grocers (think smaller shops), though making it light enough to carry will be a challenge.

Gao says that with merchants already seeing sales growth from the carts, what keeps him up at night is handling Caper’s supply chain, as the product requires a ton of different component manufacturers. The startup has to move fast if it wants to be what introduces Main Street to autonomous retail. But no matter what gadgets it builds in, Caper must keep sight of the real-world stress their tech will undergo. Gao concludes, “We’re basically building a robot here. The carts need to be durable. They need to resist heat, vibration, rain, people slamming them around. We’re building our shopping cart like a tank.”