We all know climate change is affecting weather systems and ecosystems around the world, but exactly how and in what way is still a topic of intense study. New simulations made possible by higher-powered computers suggest that cloud cover over oceans may die off altogether once a certain level of CO2 has been reached, accelerating warming and contributing to a vicious cycle.

A paper published in Nature details the new, far more detailed simulation of cloud formation and the effects of solar radiation thereupon. The researchers, from the California Institute of Technology, explain that previous simulation techniques were not nearly granular enough to resolve effects happening at the scale of meters rather than kilometers.

These global climate models seem particularly bad at predicting the stratocumulus clouds that hover over the ocean — and that’s a big problem, they noted:

As stratocumulus clouds cover 20% of the tropical oceans and critically affect the Earth’s energy balance (they reflect 30–60% of the shortwave radiation incident on them back to space1), problems simulating their climate change response percolate into the global climate response.

A more accurate and precise simulation of clouds was necessary to tell how increasing temperatures and greenhouse gas concentrations might affect them. That’s one thing technology can help with.

Thanks to “advances in high-performance computing and large-eddy simulation (LES) of clouds,” the researchers were able to “faithfully simulate statistically steady states of stratocumulus-topped boundary layers in restricted regions.” A “restricted region” in this case means the 5×5-km area simulated in detail.

The improved simulations showed something nasty: when CO2 concentrations reached about 1,200 parts per million, this caused a sudden collapse of cloud formation as cooling at the tops of the clouds is disrupted by excessive incoming radiation. Result (as you see at top): clouds don’t form as easily, letting more sun in, making the heating problem even worse. The process could contribute as much as 8 or 10 degrees to warming in the subtropics.

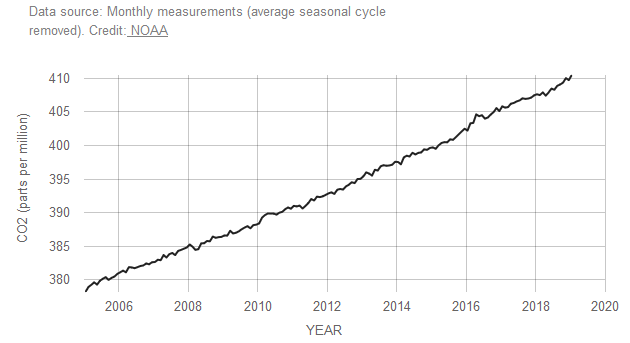

Naturally there are caveats: simulations are only simulations, though this one predicted today’s conditions well and seems to accurately reflect the many processes going on inside these cloud systems (and remember — inherent error could be against us rather than for us). And we’re still a ways off from 1,200 PPM; current NOAA measurements put it at 411 — but steadily increasing.

So it would be decades before this took place, though once it did it would be catastrophic and probably irreversible.

So it would be decades before this took place, though once it did it would be catastrophic and probably irreversible.

On the other hand, major climatic events like volcanoes can temporarily but violently change these measures, as has happened before; the Earth has seen such sudden jumps in temperature and CO2 levels before, and the feedback loop of cloud loss and resulting warming could help explain that. (Quanta has a great write-up with more context and background if you’re interested.)

“I think and hope that technological changes will slow carbon emissions so that we do not actually reach such high CO2 concentrations,” said CIT’s Tapio Schneider, lead author of the study, in a news release. “But our results show that there are dangerous climate change thresholds that we had been unaware of,”

The researchers call for more investigation into the possibility of stratocumulus instability, filling in the gaps they had to estimate in their model. The more brains (and GPU clusters) on the case, the better idea we’ll have of how climate change will play out in specific weather systems like this one.