Tunisian human rights activist Amira Yahyaoui couldn’t go to college.

Not because she couldn’t afford it; where she comes from, college is virtually free. She lost the opportunity to pursue higher education, to finish high school, even, when she was exiled from Tunisia at age 17, under the repressive regime of the country’s former President, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.

As part of the Tunisian human rights diaspora, she was inspired to build Al Bawsala, a globally renowned NGO that fights for government accountability, transparency and access to information. Now, Yahyaoui has traveled thousands of miles to San Francisco to fight another battle near and dear to her heart: civic education, or in Silicon Valley terms, edtech.

“I always knew that I wouldn’t allow myself to do anything else before solving the problem in my country and today, Tunisia is the only Arab democracy in the world,” Yahyaoui told TechCrunch.

With that in mind, her focus has shifted to Mos, a tech-enabled platform for students to apply for financial aid. With backing from Uber co-founder Garrett Camp, his startup studio Expa, Kleiner Perkins chairman John Doerr, Base Ventures, Sweet Capital and others, Mos has closed a $4 million seed round and plans to take its recently-launched product to the next level.

The startup seeks to decrease American student debt, which totaled nearly $1.6 trillion in 2018, and digitize the antiquated government systems that deter students from applying for financial aid. For a one-time fee of $149 and about 20 minutes of their time, Mos helps students of all backgrounds maximize their aid awards.

“Our mission is to bridge the gap between citizens and government in a way that works with technology today,” Yahyaoui said.

Yahyaoui is applying what she’s learned building a government-fighting NGO to the startup world, and with the support of top-tier investors, she’s well on her way to proving an “uneducated” immigrant woman of color can write a Silicon Valley success story for the masses.

A face of the Arab Spring

Mos founder and chief executive officer Amira Yahyaoui.

After being forced out of her home country, Yahyaoui fled to France, where she lived as an illegal immigrant and continued to fight against Tunisia’s authoritarian leadership through her blog and an anti-censorship campaign she started online.

When social media sparked anti-government protests across the Middle East, Yahyaoui, still unable to reenter Tunisia, became a face of what was later called the Arab Spring. Her digital prowess, activist reputation and persistent efforts to highlight the Tunisian administration’s human rights abuses quickly made her a face of the movement.

On January 14, 2011, when the protests succeeded in making Tunisia a pioneer of Arab democracy and ended Ben Ali’s reign, Yahyaoi got her passport back and went home, immediately.

Back in Tunisia with newfound freedom, she had an agenda: To hold the governing agency charged with writing a new Tunisian constitution accountable.

Yahyaoui built Al Bawsala, translated as The Compass, an NGO focused on transparency and government accountability. Al Bawsala became one of the largest NGOs in the Middle East, a bona fide success that attracted numerous awards and cemented Yahyaoui’s status as a fearless advocate for human rights, a freedom fighter and one of the most influential Arab women in the world.

“I had to work probably 10 times harder to get to be the self-educated me I am today,” she said. “I saw way too many people getting their education refused and therefore their future ruined.”

Her global standing earned her a seat on the board of the United Nation’s High Commissioner For Refugees Advisory Group on Gender, Forced Displacement, and Protection, as well as the title of Young Global Leader at the World Economic Forum and co-chair of the Davos Conference in 2016, a title she shard with Microsoft’s Satya Nadella and GM’s Mary Barra .

Three years later, with a resume enviable to any dignitary, Yahyaoui is leveraging her unique experience to lure in venture capitalists and use their cash for good.

Repairing a broken financial aid system

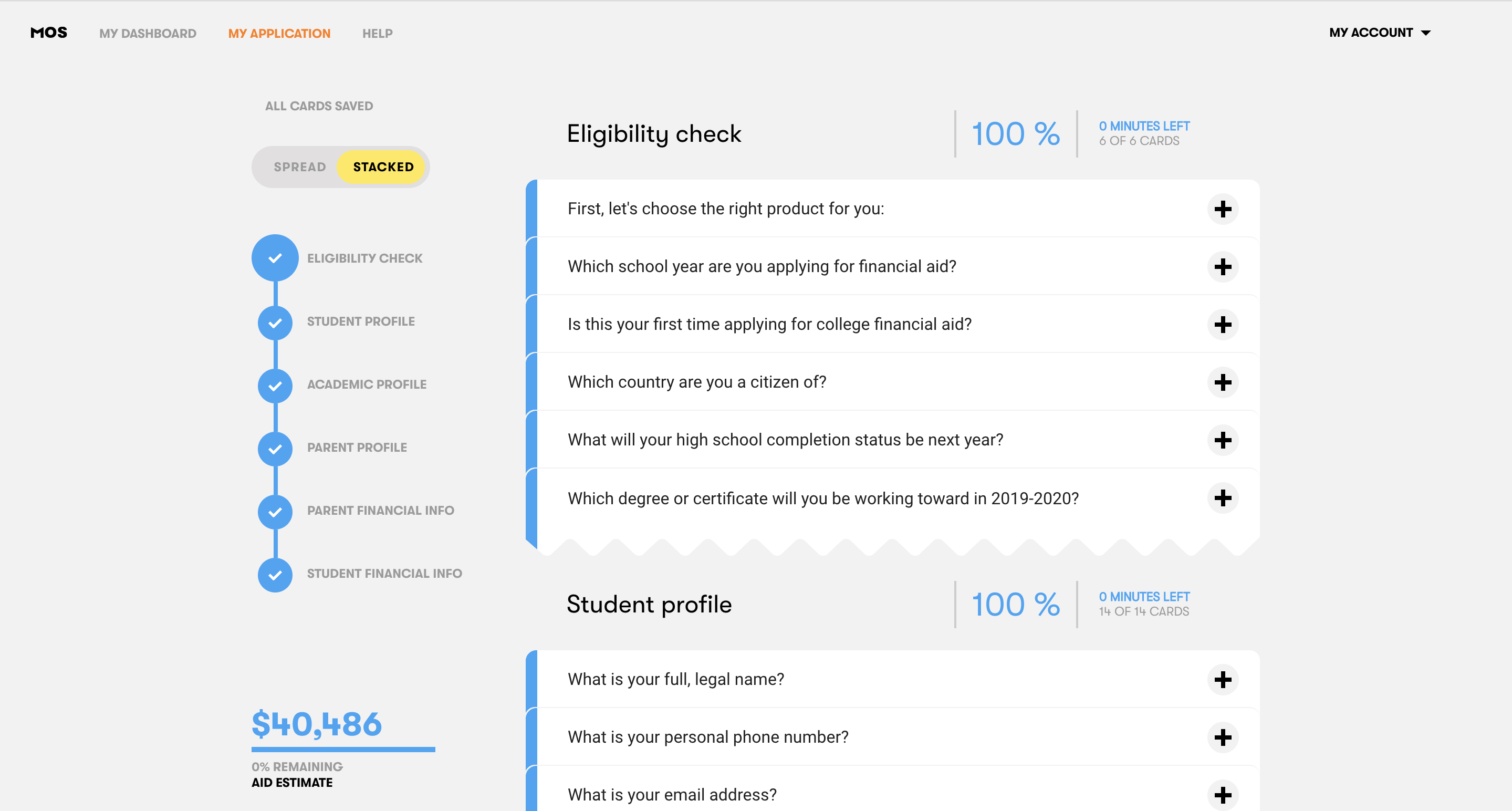

The Mos dashboard.

Mos is like if Turbo Tax married Typeform and had a baby, Yahyaoui explained. Not dissimilar to Common App, Mos lets students apply to more than 500 federal and state-based aid programs in minutes using a survey that matches them to every grant and scholarship program they qualify for, while simultaneously completing the FAFSA and state aid applications. To ensure every family is getting the most financial support possible, a Mos financial aid advisor reviews each case and negotiates with colleges for higher awards.

“Today, the biggest problem is people think they are not eligible for financial aid just because of how the thing is designed,” Yahyaoui said. “You’re supposed to just go ahead and fill a form that has 200 questions and then send it like a bottle in the sea and wait for months.”

Mos will complete a full-scale launch this summer and eventually tackle other nation’s college financial aid systems thanks to the new infusion of capital and the high-profile relationships Yahyaoui has forged in just one year living in the Bay Area.

Ultimately, it was Yahyaoui’s activism that granted her a ticket into the opaque world of Silicon Valley VC. As it turns out, angel investor Khaled Helioui, a fellow Tunisian immigrant in tech, was familiar with Yahyaoui’s work and when he heard she had relocated to the Bay Area to launch a technology startup, he wanted to know exactly what she was building. Today, he’s a Mos investor and board member and it was his introductions that helped Yahyaoui quickly and skillfully close her seed round.

An early angel investor in Uber, Helioui connected Yahyaoui with his friend Garrett Camp, the very wealthy co-founder and chairman of the ride-hailing giant, who was sold on Mos’s mission right off the bat.

“I think because Garrett is an immigrant, he knows what it is to suffer with bureaucracy,” Yahyaoui said. “He was a huge believer. He actually made it so easy for me because he said, okay, here’s an office, just stay and work.”

She was then introduced to John Doerr, the chairman of the esteemed VC firm Kleiner Perkins, known for his successful bets on companies like Google and Amazon. With Camp and Doerr on board, Mos didn’t struggle to raise additional capital; in fact, Yahyaoui was in an unusual position of being able to reject investors whose values and vision for Mos clearly didn’t align with hers.

Tearing down barriers

Yahyaoui, center, with the Mos team in San Francisco.

Yahyaoui isn’t in the startup business to get rich off students trying to navigate their way through the absorbently expensive process of applying to and attending college. She’s part of a growing class of founders out to prove that you can pair profits with good morals and lead venture-backed values-based businesses.

“I know if I created the same thing as an NGO, I could have already raised $100 million, but I like the accountability of business,” she said. “We can create businesses that are good for people.”

Yahyaoui’s story, from being exiled from her home country at a young age to fighting an authoritarian regime is not one that’s ever been told before in Silicon Valley.

In addition to being a trailblazing human rights advocate, she’s a woman, an immigrant, “uneducated” by Silicon Valley standards and a first-time tech founder that was able to walk into a meeting with John Doerr and walk out with a term sheet.

If she’s successful in building a global edtech business, she’ll be emblematic of the meritocratic culture The Valley has falsely claimed to uphold. Even if she’s not successful, she’ll have torn down barriers for other underrepresented founders and written a success story fitting for this new era of accountability in tech.