Wind turbines are a great source of clean power, but their apparent simplicity — just a big thing that spins — belie complex systems that wear down like any other, and can fail with disastrous consequences. Sandia National Labs researchers have created a robot that can inspect the enormous blades of turbines autonomously, helping keep our green power infrastructure in good kit.

The enormous towers that collect energy from wind currents are often only in our view for a few minutes as we drive past. But they must stand for years through inclement weather, temperature extremes, and naturally — being the tallest things around — lightning strikes. Combine that with normal wear and tear and it’s clear these things need to be inspected regularly.

But such inspections can be both difficult and superficial. The blades themselves are among the largest single objects manufactured on the planet, and they’re often installed in distant or inaccessible areas, like the many you see offshore.

“A blade is subject to lightning, hail, rain, humidity and other forces while running through a billion load cycles during its lifetime, but you can’t just land it in a hanger for maintenance,” explained Sandia’s Joshua Paquette in a news release. In other words, not only do crews have to go to the turbines to inspect them, but they often have to do those inspections in place — on structures hundreds of feet tall and potentially in dangerous locations.

Using a crane is one option, but the blade can also be orientated downwards so an inspector can rappel along its length. Even then the inspection may be no more than eyeballing the surface.

“In these visual inspections, you only see surface damage. Often though, by the time you can see a crack on the outside of a blade, the damage is already quite severe,” said Paquette.

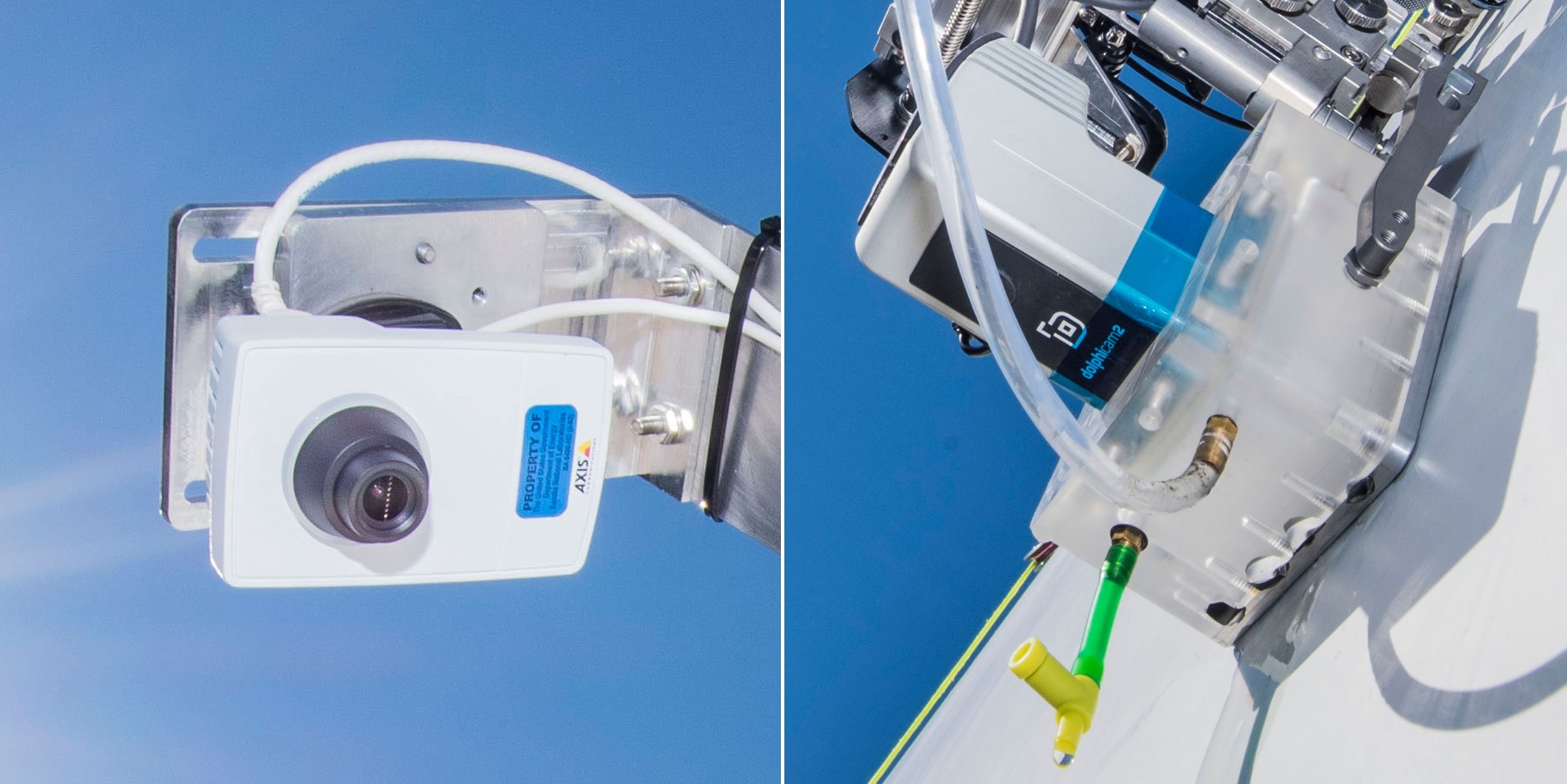

Obviously better and deeper inspections are needed, and that’s what the team decided to work on, with partners International Climbing Machines and Dophitech. The result is this crawling robot, which can move along a blade slowly but surely, documenting it both visually and using ultrasonic imaging.

A visual inspection will see cracks or scuffs on the surface, but the ultrasonics penetrate deep into the blades, making them capable of detecting damage to interior layers well before it’s visible outside. And it can do it largely autonomously, moving a bit like a lawnmower: side to side, bottom to top.

A visual inspection will see cracks or scuffs on the surface, but the ultrasonics penetrate deep into the blades, making them capable of detecting damage to interior layers well before it’s visible outside. And it can do it largely autonomously, moving a bit like a lawnmower: side to side, bottom to top.

Of course at this point it does it quite slowly and requires human oversight, but that’s because it’s fresh out of the lab. In the near future teams could carry around a few of these things, attach one to each blade, and come back a few hours or days later to find problem areas marked for closer inspection or scanning. Perhaps a crawler robot could even live onboard the turbine and scurry out to check each blade on a regular basis.

Another approach the researchers took was drones — a natural enough solution, since the versatile fliers have been pressed into service for inspection of many other structures that are dangerous for humans to get around: bridges, monuments, and so on.

These drones would be equipped with high-resolution cameras and infrared sensors that detect the heat signatures in the blade. The idea is that as warmth from sunlight diffuses through the material of the blade, it will do so irregularly in spots where damage below the surface has changed its thermal properties.

As automation of these systems improves, the opportunities open up: A quick pass by a drone could let crews know whether any particular tower needs closer inspection, then trigger the live-aboard crawler to take a closer look. Meanwhile the humans are on their way, arriving to a better picture of what needs to be done, and no need to risk life and limb just to take a look.