California’s tourism bubble has burst, an economic victim of the coronavirus outbreak.

It’s hard to chat about commerce when the key issue is the largely unknown scope and impact of a killer virus. But when financial markets are tanking, as they did again on Monday, and travel is slowing to a crawl, the monetary fallout seems fair game.

Look at what’s at stake: A globe’s worth of folks come to California for pleasure and work. The rush created surprising and outsized business opportunities in and around tourism, an industry that was hammered by the Great Recession.

Tourism, both statewide and globally, made a quick and strong rebound from the financial debacle of the late 2000s. Industry insiders and analysts alike certainly didn’t see the new consumer fervor for travel “experiences” coming. Also missed by the gurus was a solid revival in business travel, corporate expenditures once perceived as a dinosaur at risk in a modern age of communications.

This stunning tourism turnabout flooded the industry with opportunities that were met with hard cash: Billions were spent on everything from new hotels and theme park expansions to a sizable hiring spree. Folks who were impatient bought their way in, most notably with an acquisition wave that pushed hotel values to record heights.

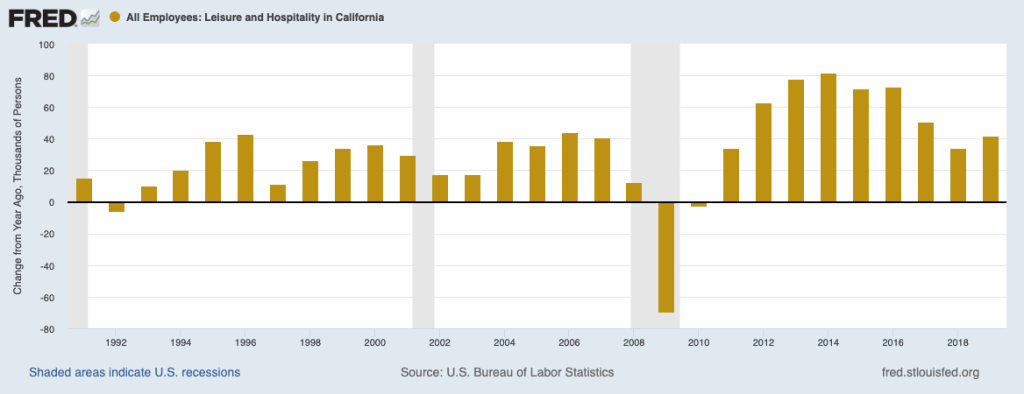

But tourism had been cooling, not crashing, well before anyone knew of a novel virus quietly stirring in China. For example, hiring in California leisure and hospitality businesses has been halved in the past two years. Disneyland’s billion-dollar bet on a Star Wars attraction wasn’t exactly met with a rabid response. And hotel buyers have pulled back on property acquisitions.

But today, all of tourism’s sizzle is gone. The U.S. government has basically warned folks to avoid most non-essential travel.

Trade shows, like a massive food conference set for Anaheim last week, have been “postponed.” Events, such as a tennis tournament set for the Coachella Valley this week, have been canceled. Cruises? Dead.

And this will become the norm for the foreseeable future.

Big bucks

It adds up to a huge economic blow as the travel business has become more than just dollars at the tourism traps.

I’m rarely a fan of industry generated “economic impact” reports, since the self-defined math often overstates the clout. Still, the VisitCalifornia trade group’s latest study, for 2018, gives us a glimpse into what kind of dollars are at being lost statewide.

The industry’s big number is California’s “total direct travel spending,” a tally of all the cash tourists spend within the state. In 2018, it was $140.6 billion, up 42% in eight years.

Tourism looks mostly modest by this math, as California’s non-inflation adjusted gross domestic production, a key measure of total business production, rose 50% in the same period to $3 trillion.

But then, look at jobs. Tourism employed 1.16 million Californians in 2018 when you add up all sorts of work directly linked to tourism. That was up 32% in 2010-18. Compare that hiring with 20% job growth in all California industries.

Ponder this job boom this way: Tourism added 281,000 jobs in eight years as California employment grew by 2.9 million. That’s almost 10% of all statewide hires for an industry that employs less than 7% of all California workers.

And remember tourism’s awkward issue: It doesn’t pay like a boom business. The average annualized pay of all California leisure and hospitality workers (a government employment grouping larger than tourism) was $36,700 at year-end 2018, roughly half the typical statewide wage.

Now, if that amount of tourism spending at risk doesn’t make you gulp enough, economically speaking, here’s what VisitCalifornia detailed as “secondary impacts.” The re-spending of travel industry cash by businesses and employees — some 795,000 additional Californians.

Hotel hotness

Nowhere in tourism did the boom change thinking more than in the hotel business as building and buying took off.

Between 2017 and 2019, California hotel owners added 29,000 new rooms, according to Atlas Hospitality. In the previous seven years? Just 23,000.

Those who bought, not built, acquired 297 California hotels worth $6 billion last year, Atlas reported. Now that’s down by one-third, in deals and dollars spent, from the 2014-15 peak. But 2019 was triple the buying pace of 2010.

This building and buying binge looks poorly timed today. The Dow Jones index of hotel-owning real estate trusts shows these stock prices slashed by one-third in the past month.

Alan Reay, Atlas’ president, says we’ll now see which operators had solid business plans that can withstand turmoil and which ones had no room for error. Yes, Reay says there are some panic responses going on. But serious business is being lost.

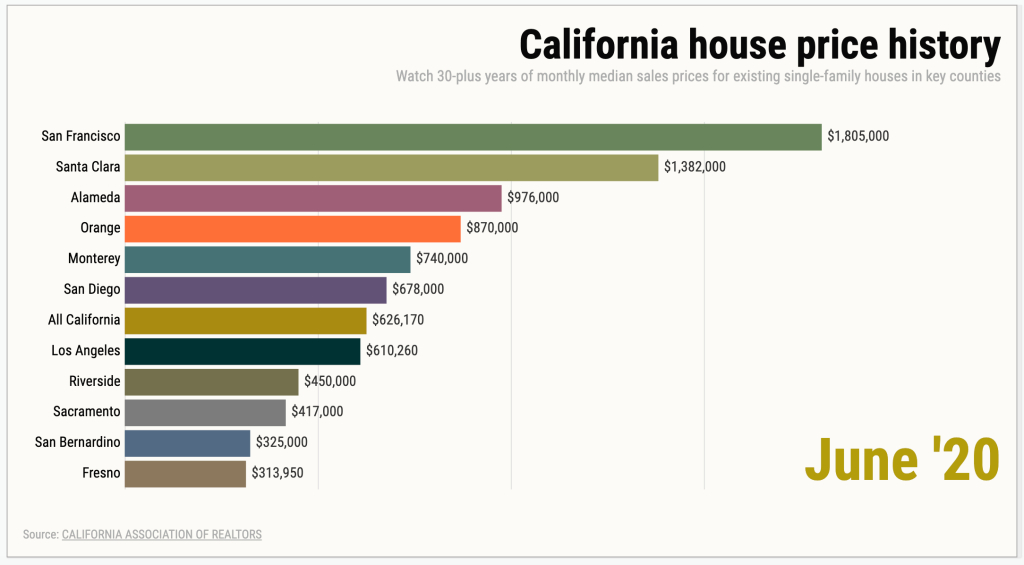

Reay mentioned that one 300-room Orange County hotel was initially overbooked last week. When the food expo was postponed, just 16 rooms were paid for.

Reay says many businesses outside of tourism will just be sitting on unexpected inventory during this economic disruption, products they can later sell. In tourism, “once the day is over, that business is gone forever,” he said.

Taxing proposition

Roughly 60% of California tourism comes from folks who live either elsewhere in the nation or internationally, according to VisitCalifornia. So even if consumers or corporations continue to travel locally — and the collapse of global crude oil prices should make gasoline eventually much cheaper — statewide tourism losses will be significant.

And if all this tourism tumult isn’t even economic wallop, the industry’s tumble won’t just hit the industry, its workers and those folks loosely tied to it.

Let’s not forget statewide tourism-related tax collections for state and local government, as calculated by VisitCalifornia. Tourism companies, employees and visitors paid everything from income taxes to sales tax to hotel levies totaling $11.8 billion in 2018. That was up 42% in eight years.