The Federal Reserve may be calming global financial markets, but California is suffering a medical emergency.

The Fed essentially slashed interest rates to zero. But Coronavirus and its required closures, cutbacks and social distancing have, in a matter of weeks, changed life as we know it. It’s a harsh blow to economics everywhere while putting scores of California jobs at risk.

Yes, the Fed might comfort nervous investors who now trade in the first bear markets since the Great Recession ended. Yes, central bank actions may nudge lenders to lend. But dead people, or simply unemployed ones, can’t borrow no matter the loan rates.

The Fed’s emergency action is an admission that risks to businesses are roughly as high as when the Great Recession was brewing, a financial meltdown central bankers couldn’t halt.

In 2020, the Fed — and all economic policymakers — face very different fear. This killer virus comes with business-sapping preventative measures — closing certain businesses and having everybody stay at home for weeks. Maybe months. I’m not sure how ultra-low interest rates will help bosses make payroll or get checkbooks to balance.

Most California jobs are already subject to some change: From outright layoffs to reduced pay to altered working conditions. So the big question is how long does it take for the state, nation — and even the planet — to mitigate this health menace and return economic activity to some level of normalcy?

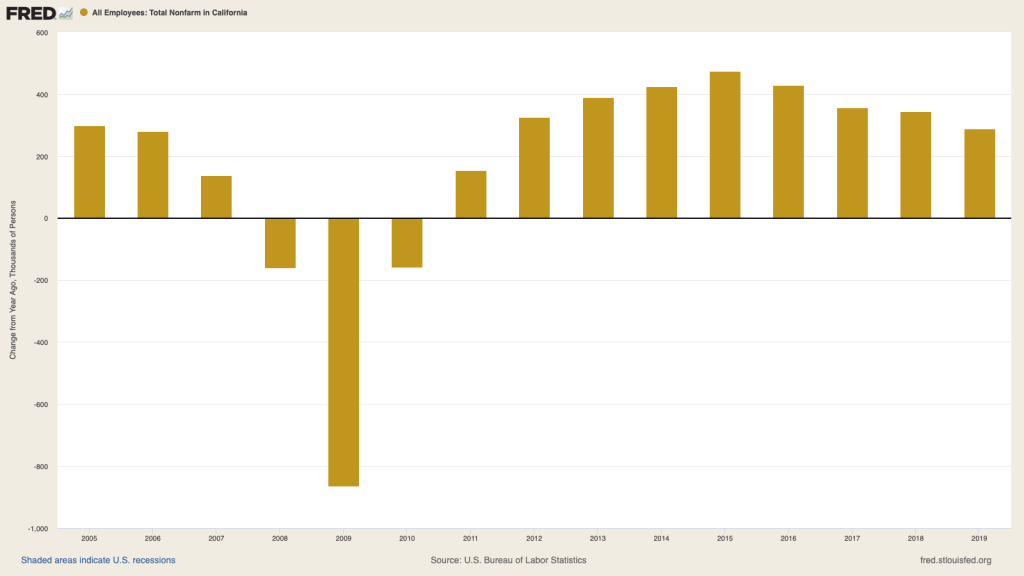

Go back to 2009, when market mayhem hit California will full force. Employers cut 800,000 workers — 1-in-20 of all jobs — in 12 months. And that came as the Fed slashed rates to levels now repeated and Congress poured billions into an economy that, at a minimum, had normal functionality.

So, allow me to handicap the Fed’s chance of helping key California job niches, with sobering reminders of 2009’s damage.

Construction and finance: These 1.75 million California workers are a clear beneficiary of the Fed’s action. Cheap money and stable financial markets will keep many development plans and real estate deals on target, helping workers at construction sites, banks and brokerages stay employed.

That’s a big plus for the economy since these workers have average annualized wages of $85,500. It would also be quite a reversal for this niche, which was battered by the Great Recession, losing 191,600 jobs — that’s 12% — in 2009 alone.

Manufacturing: Some of these 1.3 million workers, with $89,000 yearly wages, could be aided by central bank action — such as those at factories making essential goods for domestic consumption. With overseas economies tanking, most export-related work will be curtailed.

History here isn’t kind. In 2009, California manufacturers cut 130,800 jobs or 10% of all workers.

Professional/business services: These 2.7 million workers help manage and plan California businesses, from accountants and consultants to engineers and designers. This work pays well — averaging $89,000 yearly — but is often hit hard when businesses need to slash costs. Cheaper loans won’t save much. This niche lost 144,400 jobs (that’s 7%) in 2009.

Trade, transportation, utilities: These 3 million workers are the grease that makes the economy run smoothly — from longshoremen and truckers to the folks keeping the lights on and water flowing.

Nobody’s shipping anything internationally, so unless you’re moving goods for daily life, the outlook is grim. The Fed can’t help much, either. This sector’s jobs, paying $53,600 yearly, are at severe risk just like in 2009, when 167,600 were cut, or 6% of the workforce.

Information: These 552,600 million workers are a tiny but important niche because these jobs average $178,300 a year in wages. The creative slice of these workers — think: entertainment — could be pruned by health restrictions.

Keeping the Internet humming and filled with information could be a good business these days. But back in 2009, this segment lost 21,700 jobs or 5% of staffing.

Leisure and hospitality: Ugh! Deep trouble head for 2 million workers. Cheap loans can’t paper over the shuttering of theme parks, sports arenas and even neighborhood bars.

Yes, this work doesn’t pay well — with average annualized wages of $30,800 — and these folks often have little financial flexibility. This won’t be like 2009 when these industries lost only 59,600 jobs — a relatively modest 4% drop.

Education, medical, other services: These 3.3 million workers, who average $51,000 in pay, range from private school teachers (pre-school to college to trade schools) to health care (home-care providers to hospital staff) to a collection of other service workers.

Cheap money makes zero difference to health workers, a hot job amid this medical emergency. But the Fed can’t reopen schools. So, this niche won’t replicate 2009 when it added (yes, added) 7,200 jobs.

Government: The slice of the 2.5 million people providing public services required to keep Californians safe and healthy is badly needed. The future of other paychecks (government workers statewide average $73,000 salaries) could be dicey, especially as the broad business slowdown straps government budgets. In 2009, 61,000 jobs were cut, or 3% of government workers.