Now that I’ve offered an overview to help you think through where concentrated stock sits in your overall plan, let’s take a closer look at why selling can be challenging for some.

In the following section, I reveal the facts of the concentrated stock “get rich” myths that reside in the minds of many first-time concentrated stock owners, and I show why it is prudent to consider greater diversification.

Keep reading to learn more about the benefits of diversification, discover how much company stock is likely too much to hold, and the options you have when it comes to diversifying strategically.

Dangers of concentration

There are several hard facts to keep in mind in contemplating maintaining a concentrated position:

- It’s stating the obvious, but not all stocks are AAPL or AMZN. Hendrik Bessembinder published research that found the best performing 4% of listed companies explained the returns for the entire U.S. stock market since 1926. The remaining 96% of stocks collectively matched the performance of U.S. Treasury bills. Since 1926, 58% of stocks have failed to beat one-month Treasury bills over their lifetimes. Forty percent of all Russell 3000 (an index of the 3000 largest publicly traded companies in the U.S.) have lost at least 70% of their value from their peak since 1980.

- Despite all this, broad-based equities have returned 9%+ a year, beating most other asset classes, ultimately due to the top 4% of stocks. Although there is no guarantee anyone can single out any of the top 4% going forward, diversification will guarantee you will own the top 4%.

- Even if the concentrated stock you own will be another AAPL/AMZN, both stocks have experienced declines of 90%+ at some point throughout their lifetimes. Most investors would not be able to have conviction and stay invested, especially if that concentrated stock was driving the majority of their portfolio returns and net worth. Sometimes catastrophic declines are a function of the industry or existential threats that have little to do with the company itself. Other times, it has everything to do with the company and nothing to do with external factors.

The odds of any new IPO being among the top 4% is just slightly better than hitting your lucky number on the roulette wheel. But is your investment portfolio success and the odds of achieving your long-term financial goals something you want to spin the wheel on?

Benefits of diversification

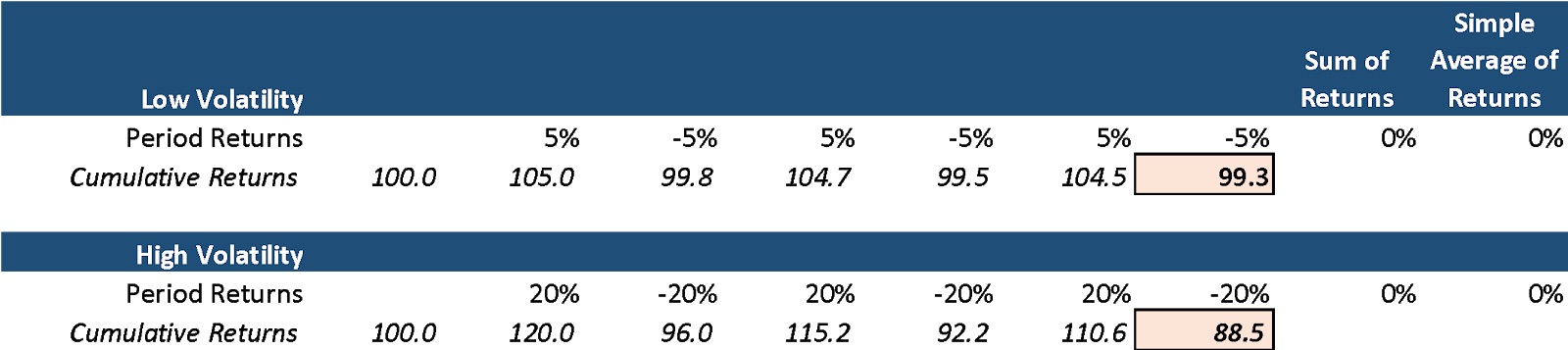

Excess volatility can harm returns. Note the example below that shows the comparison between a low-volatility diversified portfolio versus a high-volatility concentrated portfolio. Despite the same simple average return, the low-volatility portfolio below materially outperforms the high-volatility portfolio.

Image Credits: Peyton Carr

Beyond the math, unexpected spikes in volatility can cause significant price declines. Volatility increases the chances that an investor reacts emotionally and makes a poor investment decision. I’ll cover the behavioral finance aspect of this later. Lowering your portfolio volatility can be as simple as increasing your portfolio diversification.

The Russell 3000, an index representing the 3,000 largest U.S.-based publicly traded companies, has lower volatility when compared against 95%+ of all single stocks. So, how much return do you give up for having lower volatility?

According to Northern Trust Research, the 5.96% annualized average return of the Russell 3000 is 0.73% more than the 5.23% return of the median stock. Additionally, owning the Russell 3000, rather than a single stock, eliminates the likelihood of catastrophic loss scenarios — more than 20% of shares averaged a loss of more than 10% per year over a 20-year time frame.

If this establishes that the avoidance of overly concentrated portfolios is important, how much stock is too much? And at what price should you sell?

How much of your company’s stock is too much?

We consider any stock position or exposure greater than 10% of a portfolio to be a concentrated position. There is no hard number, but the appropriate level of concentration is dependent on several factors, such as your liquidity needs, overall portfolio value, the appetite for risk and the longer-term financial plan. However, above 10% and the returns and volatility of that single position can begin to dominate the portfolio, exposing you to high degrees of portfolio volatility.

The company “stock” in your portfolio often is only a fraction of your overall financial exposure to your company. Think about your other sources of possible exposure such as restricted stock, RSUs, options, employee stock purchase programs, 401k, other equity compensation plans, as well as your current and future salary stream tied to the company’s success. In most cases, the prudent path to achieving your financial goals involves a well-diversified portfolio.

What’s stopping you?

Facts aside, maintaining a concentrated position in your company stock is far more tempting than taking a more measured approach. Token examples like Zuckerberg and Bezos tend to outshine the dull rationale of reality, and it’s hard to argue against the possibility of becoming fabulously wealthy by betting on yourself. In other words, your emotions can get the best of you.

But your goals — not your emotions — should be driving your investment strategy and decisions regarding your stock. Your investment portfolio and the company stock(s) within it should be used as tools to achieve those goals.

So first, we’ll take a deep dive into the behavioral psychology that influences our decision-making.

Despite all the evidence, sometimes that little voice remains.

“I want to hold the stock.”

Why is it so hard to shake? This is a natural human tendency. I get it. We have a strong impetus to rationalize our biases and not believe we are vulnerable to being influenced by them.

Becoming attached to your company is common, since after all, that stock has made you, or has the potential of making you wealthy. More often than not, selling and diversifying is the tough, but more rational decision.

Numerous studies have furnished insights into the correlation between investing and psychology. Many unrecognized psychological barriers and behavioral biases can influence you to hold concentrated stock even when the data shows that you should not.

Understanding these biases can be helpful when deciding what to do with your stock. These behavioral biases are hard to spot and even harder to overcome. However, awareness is the first step. Here are a few more common behavioral biases, see if any apply to you:

Familiarity bias: Familiarity is likely why so many founders are willing to hold concentrated positions in their own company’s stock. It is easy to confuse the familiarity with your own company with the safety in the stock. In the stock market, familiarity and safety are not always related. A great (safe) company sometimes can have a dangerously overvalued stock price, and terrible companies sometimes have terrifically undervalued stock prices. It’s not just about the quality of the company but the relationship between the quality of a company and its stock price that dictates whether a stock is likely to perform well in the future.

Another way this manifests is when a founder has less experience with stock market investing and has only owned their company stock. They may think the market has more risk than their company when in actuality, it is usually safer than holding just their individual position.

Overconfidence: Every investor is exhibiting overconfidence when they hold an overly concentrated position in an individual stock. Founders are likely to believe in their company; after all, it already achieved enough success to IPO. This confidence can be misplaced in the stock. Founders often are reluctant to sell their stock if it has been going up since they believe it will continue to go up. If the stock has sold off, the opposite is true, and they are convinced it will recover. Often, it is challenging for founders to be objective when they are so close to the company. They commonly believe that they have unique information and know the “true” value of the stock.

Anchoring: Some investors will anchor their beliefs to something they experienced in the past. If the price of the concentrated stock is down, investors may anchor their belief that the stock is worth its recent previous higher value and be unwilling to sell. This previous value of the stock is not an indicator of its real value. The real value is the current price where buyers and sellers exchange the stock while incorporating all presently available information.

Endowment effect: Many investors tend to place a higher value on an asset they currently own than if they did not own it at all. It makes it harder to sell. An excellent way to check for the endowment effect is to ask yourself: “If I did not own these shares, would I purchase them today at this price?” If you are not willing to purchase the shares at this price today, it likely means you are only holding onto the shares because of the endowment effect.

A fun spin on this is to look into the IKEA effect study, which demonstrates that people assign more value to something that they made than it is potentially worth.

When framed this way, investors can make more intentional decisions on whether to continue holding concentrated stock or selling. At times, these biases are hard to spot, which is why having a second person, a co-pilot, or an advisor, is helpful.

Take control

Congratulations to those of you with a concentrated stock position in your company; it is hard-earned and likely represents a material wealth. Understand, there is no “right” answer when it comes to managing concentrated stock. Each situation is unique, so it is essential to speak with a professional about options specific to your situation.

It starts with having a financial plan, complete with specific investment goals that you want to achieve. Once you have a clear picture of what you want to accomplish, you can look at the facts in a new light and gain a deeper appreciation for the dangers of holding a concentrated position in company stock versus the benefits of diversification, considering all of the implications and opportunities involved in rational decision-making and investment behavior.

What are my choices if I want to diversify?

Most individuals understand they can simply and directly sell their equity, but there are a variety of other strategies. Some of these opportunities may be far better at minimizing taxes or better at achieving the desired risk or return profile. Some might wonder what the best timing is to sell. I will cover these topics in the final article of the series.