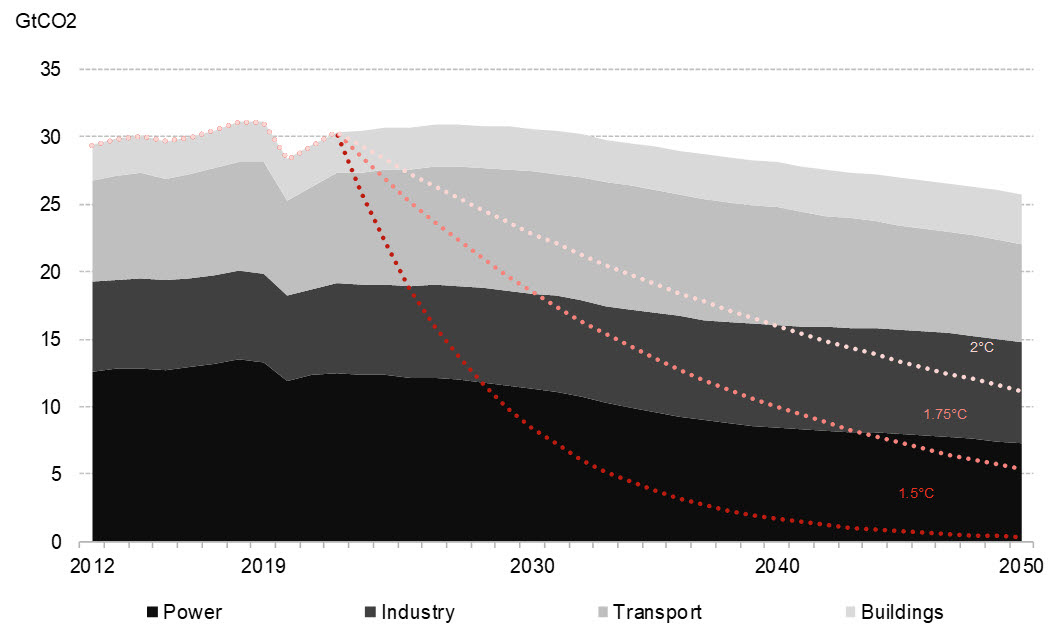

If analysts from BloombergNEF are right, then all of the world’s most greenhouse gas polluting days are behind it, thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic.

A sharp drop in energy demand caused by the global response to the coronavirus pandemic will remove 2.5 years of energy sector emissions between now and 2050, according to the latest New Energy Outlook from BloombergNEF.

The latest models from the analysis firm tracking the evolution of the global energy system show that emissions from fuel combustion will likely have peaked in 2019.

The company’s models show that global emissions declined roughly 20% as a result of the international response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and while those emissions will rise again with economic recoveries, BloombergNEF’s models never see emissions reaching 2019 levels. And from 2027 emissions are projected to fall at a rate of 0.7% per year to 2050.

Bloomberg New Energy Finance chart predicting declines in global emissions. Image Credit: BloombergNEF

These rosy projections are based on the assumption of a massive construction boom for wind and solar power, the adoption of electric vehicles and improved energy efficiency across industries.

Together, wind and solar are projected to account for 56% of global electricity generation by mid-century, and along with batteries will gobble up $15.1 trillion invested in new power generation over the next 30 years. The firm also expects another $14 trillion to be invested in the energy grid by 2050.

The rain on this new energy parade could come from India and China, which have long been reliant on coal power to keep their national economies humming. But even in these colossal coal consumers the Bloomberg report sees good news for people who like good news.

They expect coal-fired power to peak in China in 2027 and in India in 2030. By 2050, coal is projected to account for only 12% of global electricity consumption. But even with the surge in renewables, gas-fired power ain’t dead. It remains the only fossil-fuel to continue to grow until 2050, albeit at an anemic 0.5% per-year.

No one should break out the champagne based on these projections, though, because the current trajectory still sees the globe on a course to hit a 3.3 degrees Celsius rise in temperature by 2100.

“The next ten years will be crucial for the energy transition,” said Bloomberg New Energy Finance chief executive, Jon Moore. “There are three key things that we will need to see: accelerated deployment of wind and PV; faster consumer uptake in electric vehicles, small-scale renewables, and low-carbon heating technology, such as heat pumps; and scaled-up development and deployment of zero-carbon fuels.”

And a three degree rise in temperature is bad. At that temperature huge swaths of the world would be unlivable because of widespread drought, rainfall in Mexico and Central America would decline by about half, Southern Africa could be exposed to a water crisis and large portions of nations would be covered by sand dunes (including chunks of Botswana and a large portion of the Western U.S.). The Rocky Mountains would be snowless and the Colorado River could be reduced to a stream, according to this description in Climate Code Red.

“To stay well below two degrees of global temperature rise, we would need to reduce emissions by 6% every year starting now, and to limit the warming to 1.5 degrees C, emissions would have to fall by 10% per year,” Matthias Kimmel, a senior analyst and co-author of the latest report, said in a statement.