Those at risk are always vigilant for the signs of a stroke in progress, but no one can be vigilant when they’re sleeping, meaning thousands of people suffer “wake-up strokes” that are only identified hours after the fact. Zeit Medical’s brain-monitoring wearable could help raise the alarm and get people to the hospital fast enough to mitigate the stroke’s damage and potentially save lives.

A few decades ago, there wasn’t much anyone could do to help a stroke victim. But an effective medication entered use in the ’90s, and a little later a surgical procedure was also pioneered — but both need to be administered within a few hours of the stroke’s onset.

Orestis Vardoulis and Urs Naber started Zeit (“time”) after seeing the resources being put towards reducing the delay between a 911 call regarding a stroke and the victim getting the therapy needed. The company is part of Y Combinator’s Summer 2021 cohort.

“It used to be that you couldn’t do anything, but suddenly it really mattered how fast you got to the hospital,” said Naber. “As soon as the stroke hits you, your brain starts dying, so time is the most crucial thing. People have spent millions shrinking the time between the 911 call and transport, and from the hospital door to treatment. but no one is addressing those hours that happen before the 911 call — so we realized that’s where we need to innovate.”

If only the stroke could be identified before the person even realizes it’s happening, they and others could be alerted and off to the hospital long before an ambulance would normally be called. As it turns out, there’s another situation where this needs to happen: in the OR.

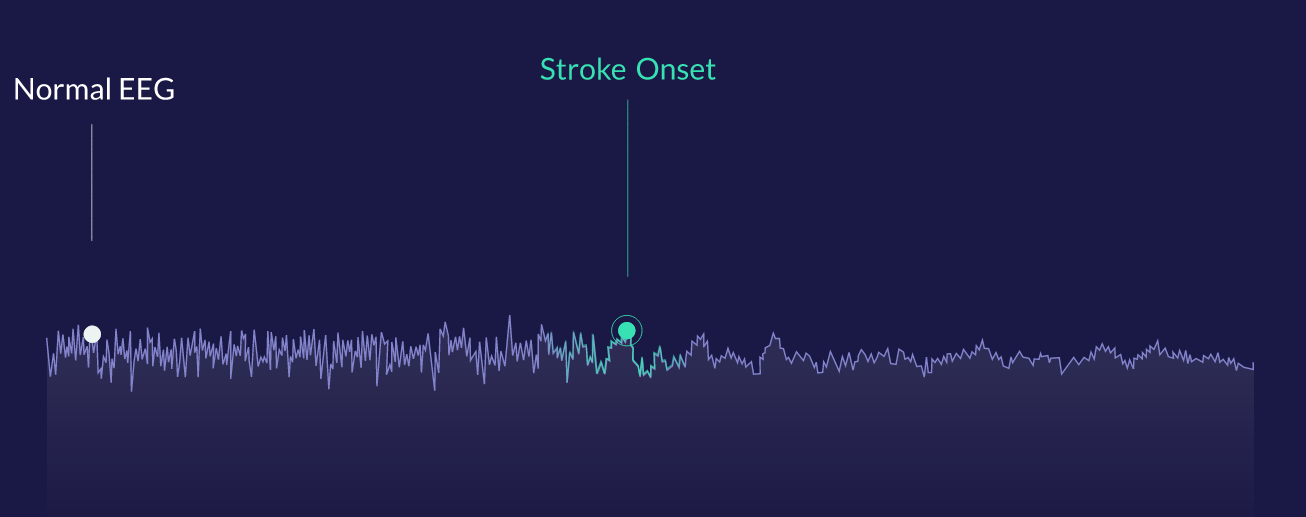

For illustrative purposes, an EEG signal that changes its character can be detected quickly by the algorithm.

Surgeons and nurses performing operations obviously monitor the patient’s vitals closely, and have learned to identify the signs of an impending stroke from the EEG monitoring their brainwaves.

“There are specific patterns that people are trained to catch with their eyes. We learned from the best neurologists out there how they process this data visually, and we built a tool to detect that automatically,” said Vardoulis. “This clinical experience really helped, because they assisted in defining features within the signal that helped us accelerate the process of deciding what is important and what is not.”

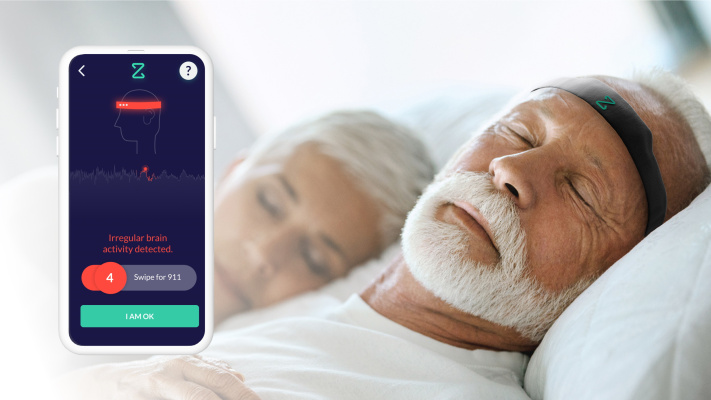

The team created a soft, wearable headband with a compact EEG built in that monitors the relevant signals from the brain. This data is sent to a smartphone app for analysis by a machine learning model trained on the aforementioned patterns, and if anything is detected, an alarm is sent to the user and pre-specified caregivers. It can also be set to automatically call 911.

“The vast majority of the data we have analyzed comes out of the OR,” said Vardoulis, where it can immediately be checked against the ground truth. “We saw that we have an algorithm that can robustly capture the onset of events in the OR with zero false positives.”

That should translate well to the home, they say, where there are actually fewer complicating variables. To test that, they’re working with a group of high-risk people who have already had one stroke; the months immediately following a stroke or related event (there are various clinically differentiated categories) is a dangerous one when second events are common.

“Right now we have a research kit that we’re shipping to individuals involved in our studies that has the headband and phone. Users are wearing it every night,” said Vardoulis. “We’re preparing for a path that will allow us to go commercial at some point in 2023. We’re working with he FDA to define the clinical proof needed to get this clear.”

They’ve earned a “Breakthrough Device” classification, which (like stroke rehabilitation company BrainQ) puts them in position to move forward quickly with testing and certification.

“We’re going to start in the US, but we see a need globally,” said Naber. “There are countries where aging is even more prevalent and the support structure for disability care are even less.” The device could significantly lower the risk and cost of at-home and disability care for many people who might otherwise have to regularly visit the hospital.

The plan for now is to continue to gather data and partners until they can set up a large-scale study, which will almost certainly be required to move the device from direct-to-consumer to reimbursable (i.e. covered by insurance). And although they are totally focused on strokes for the present, the method could be adapted to watching for other neurological conditions.

“We hope to see a future where everyone with a stroke risk is issued this device,” said Vardoulis. “We really do see this as the missing puzzle piece in the stroke care continuum.”