“If elected governor of California, one of my goals will be to slash the value of California real estate.”

Said no politician ever.

But if California is truly serious about affordable housing — and I’m becoming convinced it’s not — then somebody in the real estate world must accept less than what they have right now.

The pandemic era — not to mention a recall election campaign for the governor’s job — got many Californians rethinking housing.

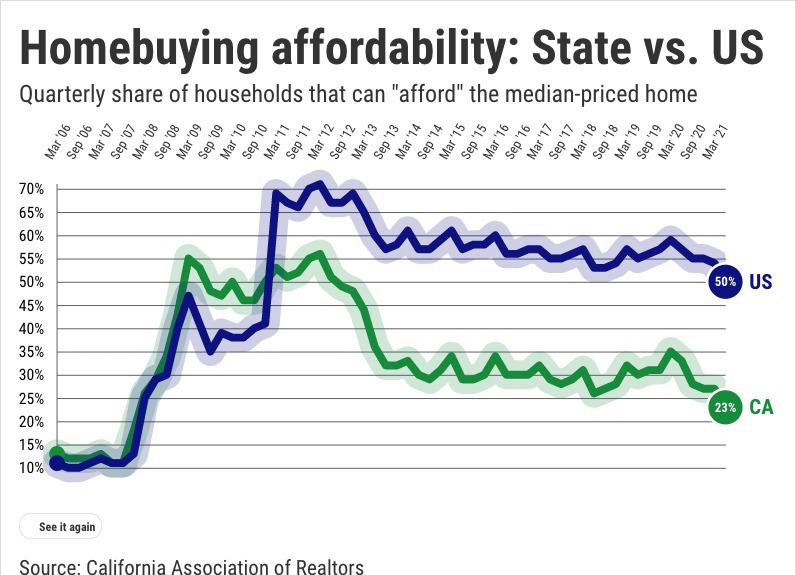

Look what’s happened. A surprising homebuying binge ballooned prices across the state. Despite historically low mortgage rates, only 23% of Californian households could afford to buy the typical house this spring, according to a California of Association of Realtors index. That’s down from 35% in 2020’s first quarter before coronavirus upended the economy and the lowest affordability rate since the end of 2007.

And note, affordability is down nationwide, too: 50% in the spring vs. 59% just before COVID-19 hit and the lowest since the end of 2010.

Policy discussion is always good. However, it’s too easy for people — from political candidates to industry know-it-alls to various pundits — to say California’s housing challenges are simple supply vs. demand issues being thwarted by government meddling.

Doesn’t Econ 101 say there’s no free lunch?

Yes, tossing government money at the problem often just raises costs by giving buyers more reasons to overpay. Yet the competing “build it and they will come/free market” logic is no panacea either.

Lifting much-maligned bureaucratic limits on California housing development — and of course, every real estate faction has their favorite rules to rescind — will create marketplace upheaval. That means winners … and LOSERS.

As a result, the economy’s primal pressures will nudge certain market participants to push back against change — and those capitalistic forces will ignore societal needs and even use their government pals to protect their interests. NIMBYs aren’t only the locals saying “not in my backyard” — it’s industry, too!

Because in Econ 101 terms, owners — big or small — want to maintain, if not increase, the value of their assets.

So to those who think “Make California Affordable Again” is easy, just tell me who pays …

Current homeowners? A California with a sudden supply of affordable housing would likely see home values fall. And Californians would have new neighbors in denser projects, whether those are in established neighborhoods or on that previously “untouchable” suburban landscape.

Owners of second homes? If we actually have a massive housing shortage (something worth debating another day), why does society still encourage people to own more than one home? If folks want a vacation home or the like, fine. But why do they get numerous tax breaks with that ownership?

Landowners? Let’s remember what typically adds the largest cost to California housing expenses — the pricey property it’s built on. If somehow large amounts of acreage were allowed to quickly get government approval to build on, the giant entities that today control developable land face a price reduction.

Investors? A big boost to the housing supply — especially rental units — translates to added competition for landlords. That would likely chill rent hikes if not depress them altogether. And we all know how hard this industry fights even modest attempts to curb rent increases. Remember, lower cash flows cut the values of these investment properties.

Builders? Despite all the industry’s complaining about rising costs in the pandemic era — from lumber to labor — profits and profit margins have soared. Builders want predictability. Affordable housing requires risk-taking and somebody constructing home types that may be less profitable. The status quo is too financially comfortable for builders.

Mortgage makers? One reason housing is unaffordable is that buyers who can afford a home also can easily get financing. Yes, we don’t want a repeat of the last easy-money bubble. Yet we need a financing system that’s fair and affordable for those people with somewhat modest means. Cutting transaction costs for those needing affordable housing would help, too.

Construction workers? Building more will require more construction workers, and they’re already in short supply. That’s pushing up salaries, boosting labor costs passed along to house hunters. But lowering salaries (accomplished, in part, by nudging unions out of the way) will limit the growth of the construction trades. That would make any hope of a significant construction surge unlikely.

Other transaction personnel? Think of a property as it goes from raw land to developable lots to sold new homes and then is resold as existing residences. Think of all the marketing involved and the real estate pros who get paid to execute those transactions. If we’re truly pondering affordability, an often ignored cost in housing market is selling it. At a minimum, how do we make these markets more transparent and open to modern thinking?

The bottom line? There is no affordable housing without financial pain. Property values must fall.

Jonathan Lansner is business columnist for the Southern California News Group. He can be reached at jlansner@scng.com