With apologies to country songwriter David Allan Coe, the 2021 job market’s theme song is “Take This Job and Quit It.”

In September, 4.3 million U.S. workers quit their jobs, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the highest number on record and evidence of the public’s broad rethinking of employment and whether it’s a worthwhile endeavor.

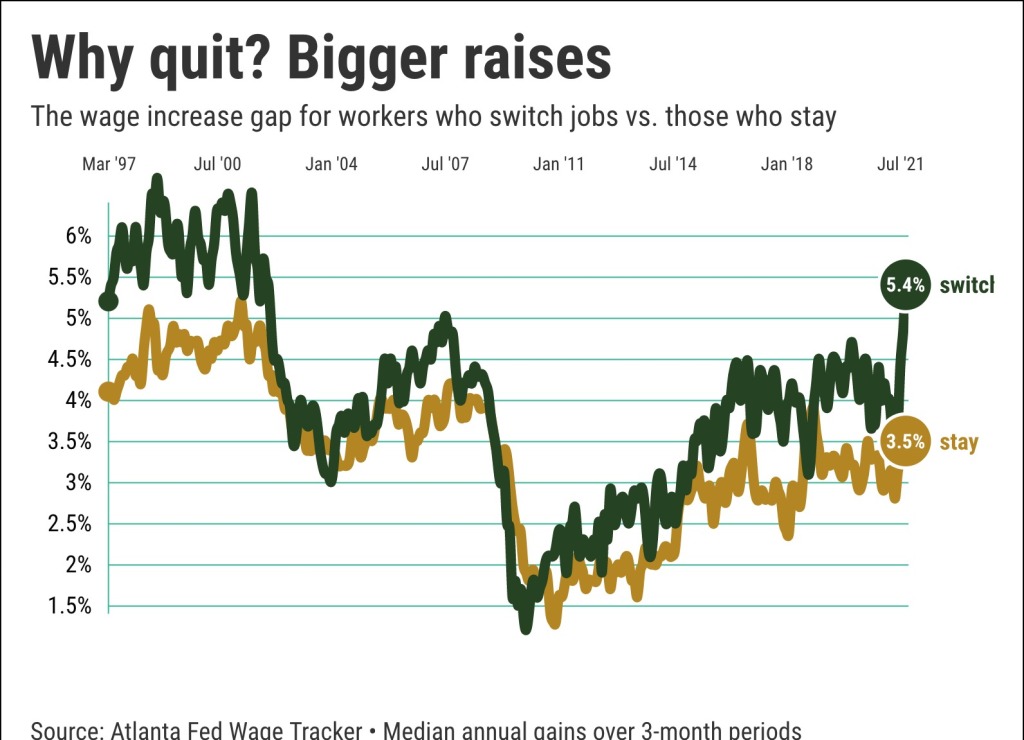

Why is the “I’m outta here” movement such a hot workplace trend? The easiest way to get a better raise these days is to switch jobs.

This unfortunate career tactic is bolstered by my trusty spreadsheet’s review of detailed wage stats from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

Job switchers — those changing employers or job duties or going to a different occupation or industry — got a median 5.4% annual wage increase during the three months ended in September.

Now, compare that with folks keeping their jobs, who only saw their wages go up 3.5%. Or overall U.S. wage growth at 4.2%.

This is the largest gap between raises for “switchers” and “stayers” in 23 years. Talk about a incentive to quit.

So perhaps bosses should ask themselves if they’re part of the problem.

Hunt for raises

Workplace analysts, policymakers and business leaders have debated the motivations behind all the quitting.

Suggested factors range from fear of catching coronavirus on the job to plenty of openings to choose from and a lack of childcare for younger members of the workforce. The seemingly illogical tactic of bosses paying up for a new person vs. giving existing staff more cash has to be part of the discussion.

Stats show employers became incredibly stingy with salary raises during and after the Great Recession.

Let’s look at an odd workplace stat tracked by the Atlanta Fed: workers who got no raise at all. In the 2010 decade, wages were stagnant for 15% of the workforce. That was up from the 2000s when only 12.3% got no salary bump.

Then came the pandemic’s economic volatility, and surprisingly, workers were again valuable: The share of “no raises” fell to 13.4% by August.

We’re witnessing another chapter in the evolving give-and-take between boss and worker.

Before the pandemic, career stability and workplace culture — rather than pay — felt like the most-desired traits. Workers focused on higher pay were often forced to job hunt while bosses got their stable flock ping-pong tables and gourmet coffee machines.

Today, it seems like it’s all about the money. Let’s look at the varying size of the financial carrot offered to those claiming a new job.

From 1998 to 2007, the bubble-fueled boom years, job switchers got 4.9% raises vs. 4.1% for those who didn’t. That’s a 0.8 percentage-point reason to change jobs.

When those good times turned extra sour — the Great Recession era of 2008 to 2012 — the clout of job switchers diminished with 3% raises barely ahead of 2.9% for “stayers.”

Then came the 2013-19 economic rebound and the pay-hike edge returned for switchers: 3.3% raises vs. 2.6% for stayers — a 0.7 point gap.

And these premium raises only grew in the pandemic era: Switchers averaged 4.2% raises since March 2020 vs. 3.2% — a full-point gap.

No uniform pay

So, who’s getting the better raises?

This summer only two job-market slices offered larger raises than job switching, according to my spreadsheet’s analysis of 32 worker characteristics tracked by the Atlanta Fed using 12-month moving averages.

You’d either have to be among the youngest workers — ages 16 to 24, whose typical wages jumped 9.5% in a year — or be among the lowest-paid workers, who got 4.8% raises.

Workers in hard-to-fill, entry-level or poorly-paying positions got nearly the same pay hikes as quitters. Pay for leisure and hospitality industries rose 3.9% in a year while workers without college degrees and those in “low skill” positions got 3.8% pay hikes.

And only the two groups got smaller raises than people who stayed with their employer. The highest-paid workers got just 2.8% raises while the oldest workers, age 55 or higher, got only 1.9%.

Bosses are learning that workers know pay jumps if you jump ship, especially for low-wage positions. And in 2021, it’s all about the paycheck.

Quitting is the new labor movement.

Jonathan Lansner is business columnist for the Southern California News Group. He can be reached at jlansner@scng.com