“Bubble Watch” digs into trends that may indicate economic and/or housing market troubles ahead.

Buzz: The stock market is officially in a bear market downturn, and that’s rarely good news for California’s economy.

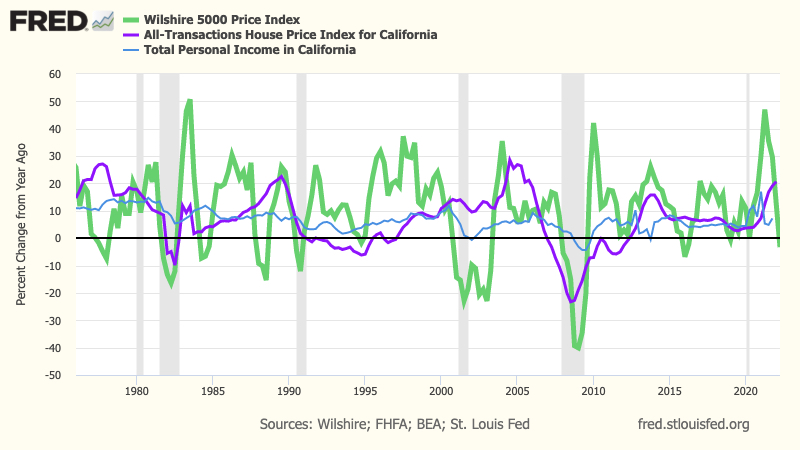

Source: Using the definition of a bear market as a 20% drop in the S&P 500 stock index, my trusty spreadsheet looked at what followed the start of the five such Wall Street downturns before the pandemic. To gauge the fallout, I looked at California’s economy in terms of the 12-month change in unemployment, jobs, total statewide personal income, home prices (FHFA index) and 30-year mortgage rates.

The Trend

Wall Street’s latest bear market officially started in January. In the past, California’s economy typically reacted lethargically, at best.

In the year following the start of these five deep market dives, California’s unemployment rose on average to 7.6% from 6.1%. Meanwhile, growth cooled for jobs (to 0.2% from 2.1%), income (2.1% from 7.7%) and home prices (0.9% from 5.1%).

With a backdrop of weakness spreading from Wall Street as far as the Pacific Coast Highway, borrowing costs fell. Mortgage rates dipped on average by 1.3 percentage points in a year.

The dissection

Ponder these five bear markets and how they played out in California.

November 1980 through August 1982, 27% stock losses: Geopolitical turmoil, notably an Arab oil embargo, a change in presidents (from Jimmy Carter to Ronald Reagan), and inflation-bashing double-digit interest rates sent stocks into a dive. Wall Street’s pain certainly foreshadowed brewing economic distress in California.

A year after this bear market started, California unemployment rose to 11% from 8.2% as the jobs count morphed from 0.7% growth to a 2.2% decline. Statewide income growth went from 9.9% to a near standstill at 0.7%.

Home prices that at this bear market’s start were rising 8.4% shifting to a 1.4% loss 12 months later. And that fall came despite mortgage rates falling to 14% from 17.7%.

August 1987 through December 1987, 34% stock losses: The rebound out of the dark days of the early 1980s ended abruptly seven years later, highlighted by the Black Monday stock crash in October.

Curiously, the California economy was largely spared any fallout in the year after this bear market started.

Unemployment fell to 5.3% from 5.6% as job growth quickened to 3.8% from 3.4%. Income growth did cool — 3.4% from 7.3% — but stock losses were likely part of that chill.

Homes looked like a haven from these stock gyrations. Annual appreciation ballooned to 16.3% from 11% as mortgage rates flattened at what seemed to be a bargain those days — 10.5%.

July 1990 through October 1990, 20% stock losses: The economy may have ignored the stock drama of 1987 and 1989, but the Golden State business machine eventually ran out of steam in the early 1990s recession.

This brief and modest bear market was definitely felt in California in the year following and beyond. Unemployment jumped to 7.9% from 5.9% and 2.5% job growth became a dip of 1.3% a year. Income growth chilled, too, to 2.5% from 7.8%.

And this was also the beginning of the 1990s housing malaise. Home prices gains of 5.6% became 1.3% losses 12 months after the market stall. Falling rates — 9.3% from 10.1% in the year after the bear market started couldn’t prevent six more years of home-price declines that followed.

March 2000 through October 2002, 49% stock losses: Wall Street dusted off the early 1990s downturn far quicker and more robustly than California’s economy.

Investors flocked to technology’s “dot-com” stocks with a bubbly fervor. When that error was corrected, a swift and deep bear market emerged. Yet California’s broad economy suffered just modest damage from this Wall Street debacle.

This disconnect is especially curiously considering the bear market was heavily tied to the crashing shares of many of the state’s technology companies.

A year after the bear market started, statewide unemployment dipped to 4.8% from 5%. However, there was a chill in job growth, slipping to 3.1% from 3.4% and income growth, which fell to 3.4% from 9.6%.

Home prices again flourished amid uncertainty with 10.9% gains growing to 13.6%. Falling mortgage rates helped, too, dropping to 7% from 8.3% a year later.

October 2007 through March 2009, 57% stock losses: Housing’s escape from the dot-com stock rout oddly may have helped create the foundation for the giant stock and economic tumble into the Great Recession.

The overindulgence of tech stocks switched to an unhealthy passion for housing. A giant real estate bubble superheated the entire economy. Well, until this irrational exuberance collapsed into a global downturn.

In the year after the bear market started, California unemployment went to 8.8% from 5.7%. Job growth of 0.6% turned into a 2.6% yearly loss. Income growth of 4% all but evaporated to 0.6%.

Please note that housing was a mess before stocks officially were in bear market status. California home depreciation exploded into 22.7% losses from 10.4% a year later despite rates falling to 5.8% from 6.2%.

How bubbly?

On a scale of zero bubbles (no bubble here) to five bubbles (five-alarm warning) … FIVE BUBBLES!

There’s a mistaken notion that stocks are somehow removed from broad economic realities. These days, we watch them around the clock, and their volatility can make it feel like a casino. But you cannot ignore Wall Street’s dips.

Sinking stocks typically trim investors’ appetite for risk. That hurts California businesses, which happen to thrive on risk-taking.

Bear markets also unnerve C-suite types whose anxieties often morph into layoff-minded thinking.

Those kinds of reactions also damage consumer spending habits along with shrinking portfolios.

It’s a recipe for a chilly California business climate. Remember, this state’s economy was smacked as Wall Street was bitten by three of the last five bear markets.

And I’d argue after the two other stock fiascos — 1987 and 2000 — California’s economy was very lucky. The real estate bubbles of those eras simply delayed the eventual economic pain.

Sounds a bit like 2022?

Jonathan Lansner is the business columnist for the Southern California News Group. He can be reached at jlansner@scng.com