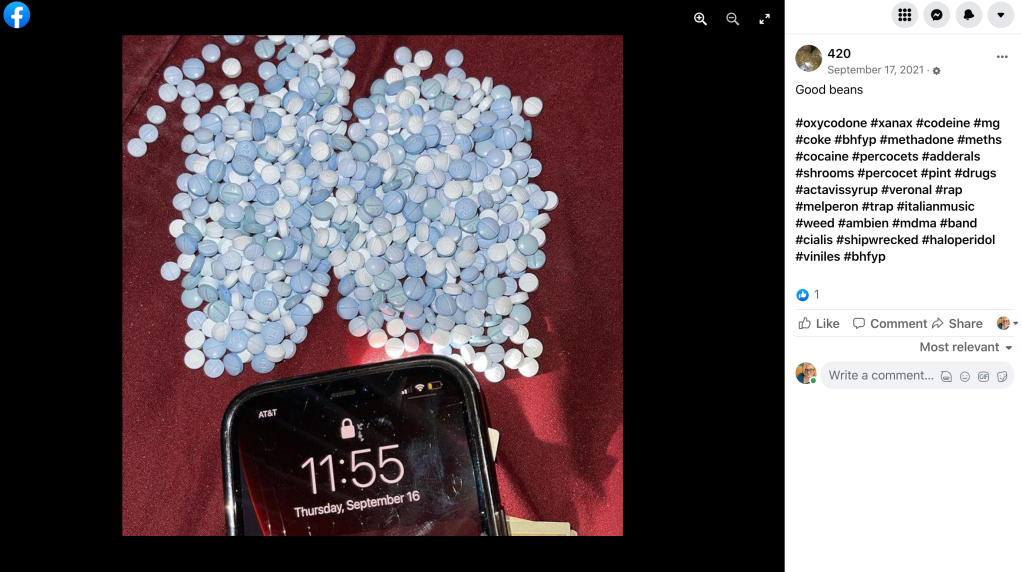

Subtle they’re not. “Good beans,” the Facebook post said, beside a cascade of blue and white pills and the words “#oxycodone, #xanax, #codeine…#percocets…#drugs…” and a string of slang I’m not hip enough to understand.

The account was reported to Facebook in May. Twice, Facebook’s moderators said it didn’t violate community guidelines.

Then there’s Melissa420pills. Satisfied customers posted videos of receiving their drug shipments via the U.S. mail and opening them on camera. That account was reported to Facebook, too, and seems to have gone dark — but Melissa420pillz apparently took its place. “As usual it’s perfect,” a person posting under the name “Satisfied buyer” enthused in a Sept. 6 video. “Three bottles of bars, 270 count, every time. Every time I order from her I have no problems ever. Thanks Melissa.”

“Bars” is slang for Xanax.

Clearly, platforms like Facebook and Snapchat are not doing enough to reduce illegal dealing on their sites, says the new Commission to Develop Best Practices for Social Media to Eliminate Drug Trafficking, spearheaded by impassioned parents like Amy Neville of Aliso Viejo and Steve Filson of Redlands. Their children died after ingesting imposter drugs containing fentanyl, bought oh so easily online.

These parents, along with academics and law enforcement types, are refusing to let the social media companies coast with promises to do better. “Best Practices to Rid Social Media of Drug Trafficking” was released on Tuesday, Sept. 27, laying out concrete steps the social media giants can take to reduce the carnage.

“We are in a war we’re not winning,” said Sheriff Kieran Donahue of Canyon County, Idaho, where he serves on the Oregon-Idaho High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area Executive Board. “The American people have to stand up and say these social media companies are complicit in these deaths.”

We’ll get to the specifics in a minute. But when we asked Meta — Facebook and Instagram’s parent company — to take a look at the report for its thoughts, we got an email listing its policies forbidding drug dealing on the platforms. A spokesperson said it’s giving parents more access to their kids’ activity online, and that it hopes a recent pilot with Snapchat — to identify illicit drug-related content and activity — eventually involves other companies “to help protect people and combat this industry-wide issue.”

But what of Melissa420pillz and the videos? Can’t artificial intelligence — or, maybe, a human being — tell when an “s” turns to a “z” on an apparent drug dealer’s account? When do policies turn into action?

Those questions weren’t answered by deadline. And Melissa420pillz was just as eager to talk.

Snapchat, where Neville’s son 14-year-old son Alex found the pill that killed him, said it’s already doing many of the things the report recommends. It promised to study the recommendations more closely and asked us to underscore that actual drug sales don’t happen on Snapchat because the platform doesn’t support fund transfers. So there’s that.

‘Adorable kitten videos’

Shabbir Safdar, executive director of the Partnership for Safe Medicines, is part of the team pushing for change. His organization reported the original Melissa account, and is appalled that its heir continues to operate openly.

So is Filson, whose daughter Jessica died at 29 thanks to adulterated cocaine. People get thrown in “Facebook jail” for political comments, but not for killing people, said Daniel Salter, director of the Atlanta-Carolina High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas Program.

“Drug traffickers use all of the tools and platforms of social media, from still images to video, with the same ease that others use them to post adorable kitten videos,” said an introduction to the report by Neville and Filson.

“Like any other kind of business, dealers use social media to recruit customers, advertise products, and drive sales. Some traffickers run small, local operations. Others operate multistate rings and coordinate sales across multiple social media channels.

“We thought that social media companies wouldn’t stand for drug traffickers on their platforms killing our children — and dozens of others. Despite our pleas, and those of so many other victims’ families, and despite the subsequent promises of almost every major social media platform, organizations who track these deaths report that the problem is still growing.

“How many more grieving parents are enough? It’s unclear when we will reach the threshold for social media giants to take meaningful action. However, platforms could act today. From our research with law enforcement, parent safety groups, and anti-child pornography advocates, we have identified concrete changes social media companies can implement now to thwart illicit drug sales.”

How?

Some suggestions:

• Rigorous enforcement of drug trafficking bans. Platforms have moved to ban child sexual abuse material and root out terrorist recruiting propaganda; they could do the same for drug dealing. They could use automated tools to identify suspect accounts, devote staff to reviewing flagged content and prevent offenders from opening new accounts.

• Help law enforcement investigations by archiving suspect content and responding to subpoenas in a timely manner. Material produced 30 and 60 days after a request may be as good as no material produced at all.

• Make it easier for users to report traffickers and get timely responses. Raise the age limit for legal social media access (13 is too young). Enable parental controls on accounts. Share data between platforms because, as Snapchat noted, transactions typically occur across multiple platforms.

• And have third-party monitoring of all these efforts. “They’ve lost the right to police themselves,” Neville said. “How dark and deep this really goes — that shook me up. We’re in very scary times, and at this point, it’s not getting any better. We need to get in deep and fix it.”

Congress can take action to make all this, and more, the law, committee members said.

“We understand that the social media giants that exist today won’t be halting all their operations to immediately implement our recommendations,” the report said. “In fact, we acknowledge that many of them will simply ignore them. However, it’s critical that we show current and future social media platforms what we expect of them.”

Snapchat says it’s listening.

“As the U.S. fentanyl epidemic continues to worsen, we are devastated for the families who have suffered unimaginable losses,” a spokesperson said by email. “We have been working tirelessly to help combat this national crisis by eradicating illicit drug dealers from our platform. We use advanced technology to proactively detect and shut down drug dealers who try to abuse our platform, and block search results for dangerous drug-related content.

“We have continued to strengthen our support for law enforcement investigations and launched new in-app tools and content to raise awareness with Snapchatters about the dangers of fentanyl and give parents insight into who their teens are friends with on our app. This fall, we will launch an unprecedented public education campaign with the Ad Council and other tech platforms focused on reaching both parents and young people. We are committed to bringing every resource to bear to keep fighting this epidemic both on our app and across the tech industry, and will be rolling out additional initiatives in the coming months.”

Facebook?