Videoconferencing has become a cornerstone of how many of us work these days — so much so that one leading service, Zoom, has graduated into verb status because of how much it’s getting used.

But does that mean videoconferencing works as well as it should? Today, a new startup called Headroom is coming out of stealth, tapping into a battery of AI tools — computer vision, natural language processing and more — on the belief that the answer to that question is a clear — no bad WiFi interruption here — “no.”

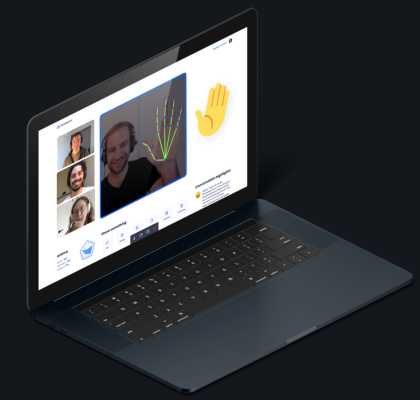

Headroom not only hosts videoconferences, but then provides transcripts, summaries with highlights, gesture recognition, optimised video quality, and more, and today it’s announcing that it has raised a seed round of $5 million as it gears up to launch its freemium service into the world.

You can sign up to the waitlist to pilot it, and get other updates here.

The funding is coming from Anna Patterson of Gradient Ventures (Google’s AI venture fund); Evan Nisselson of LDV Capital (a specialist VC backing companies buidling visual technologies); Yahoo founder Jerry Yang, now of AME Cloud Ventures; Ash Patel of Morado Ventures; Anthony Goldbloom, the cofounder and CEO of Kaggle.com; and Serge Belongie, Cornell Tech associate dean and Professor of Computer Vision and Machine Learning.

It’s an interesting group of backers, but that might be because the founders themselves have a pretty illustrious background with years of experience using some of the most cutting-edge visual technologies to build other consumer and enterprise services.

Julian Green — a British transplant — was most recently at Google, where he ran the company’s computer vision products, including the Cloud Vision API that was launched under his watch. He came to Google by way of its acquisition of his previous startup Jetpac, which used deep learning and other AI tools to analyze photos to make travel recommendations. In a previous life, he was one of the co-founders of Houzz, another kind of platform that hinges on visual interactivity.

Russian-born Andrew Rabinovich, meanwhile, spent the last five years at Magic Leap, where he was the head of AI, and before that, the director of deep learning and the head of engineering. Before that, he too was at Google, as a software engineer specializing in computer vision and machine learning.

You might think that leaving their jobs to build an improved videoconferencing service was an opportunistic move, given the huge surge of use that the medium has had this year. Green, however, tells me that they came up with the idea and started building it at the end of 2019, when the term “Covid-19” didn’t even exist.

“But it certainly has made this a more interesting area,” he quipped, adding that it did make raising money significantly easier, too. (The round closed in July, he said.)

Given that Magic Leap had long been in limbo — AR and VR have proven to be incredibly tough to build businesses around, especially in the short- to medium-term, even for a startup with hundreds of millions of dollars in VC backing — and could have probably used some more interesting ideas to pivot to; and that Google is Google, with everything tech having an endpoint in Mountain View, it’s also curious that the pair decided to strike out on their own to build Headroom rather than pitch building the tech at their respective previous employers.

Green said the reasons were two-fold. The first has to do with the efficiency of building something when you are small. “I enjoy moving at startup speed,” he said.

And the second has to do with the challenges of building things on legacy platforms versus fresh, from the ground up.

“Google can do anything it wants,” he replied when I asked why he didn’t think of bringing these ideas to the team working on Meet (or Hangouts if you’re a non-business user). “But to run real-time AI on video conferencing, you need to build for that from the start. We started with that assumption,” he said.

All the same, the reasons why Headroom are interesting are also likely going to be the ones that will pose big challenges for it. The new ubiquity (and our present lives working at home) might make us more open to using video calling, but for better or worse, we’re all also now pretty used to what we already use. And for many companies, they’ve now paid up as premium users to one service or another, so they may be reluctant to try out new and less-tested platforms.

But as we’ve seen in tech so many times, sometimes it pays to be a late mover, and the early movers are not always the winners.

The first iteration of Headroom will include features that will automatically take transcripts of the whole conversation, with the ability to use the video replay to edit the transcript if something has gone awry; offer a summary of the key points that are made during the call; and identify gestures to help shift the conversation.

And Green tells me that they are already also working on features that will be added into future iterations. When the videoconference uses supplementary presentation materials, those can also be processed by the engine for highlights and transcription too.

And another feature will optimize the pixels that you see for much better video quality, which should come in especially handy when you or the person/people you are talking to are on poor connections.

“You can understand where and what the pixels are in a video conference and send the right ones,” he explained. “Most of what you see of me and my background is not changing, so those don’t need to be sent all the time.”

All of this taps into some of the more interesting aspects of sophisticated computer vision and natural language algorithms. Creating a summary, for example, relies on technology that is able to suss out not just what you are saying, but what are the most important parts of what you or someone else is saying.

And if you’ve ever been on a videocall and found it hard to make it clear you’ve wanted to say something, without straight-out interrupting the speaker, you’ll understand why gestures might be very useful.

But they can also come in handy if a speaker wants to know if he or she is losing the attention of the audience: the same tech that Headroom is using to detect gestures for people keen to speak up can also be used to detect when they are getting bored or annoyed and pass that information on to the person doing the talking.

“It’s about helping with EQ,” he said, with what I’m sure was a little bit of his tongue in his cheek, but then again we were on a Google Meet, and I may have misread that.

And that brings us to why Headroom is tapping into an interesting opportunity. At their best, when they work, tools like these not only supercharge videoconferences, but they have the potential to solve some of the problems you may have come up against in face-to-face meetings, too. Building software that actually might be better than the “real thing” is one way of making sure that it can have staying power beyond the demands of our current circumstances (which hopefully won’t be permanent circumstances).