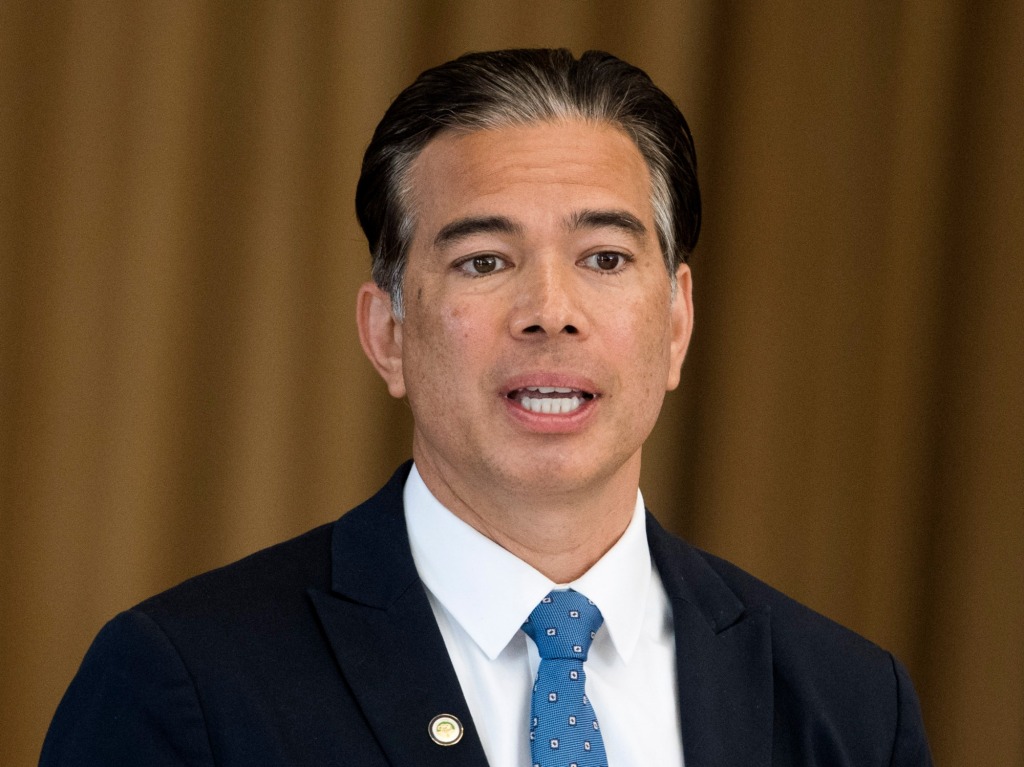

As statewide tenant protections extend through June, California Attorney General Rob Bonta announced Thursday he has warned nearly 100 law firms against filing false claims in eviction cases.

The attorney general’s housing strike force sent letters to 91 law firms in recent days, alerting attorneys not to file evictions against tenants who have applied for state emergency rental assistance. The state bans evictions for nonpayment if a tenant has applied to the state’s relief program, Housing is Key.

More than 100,000 California tenants have pending relief applications. The program was set to close at midnight March 31.

“We have reason to believe that some landlords and their attorneys may be filing false declarations to push hardworking Californians out of their homes,” Bonta said. “This is unacceptable, and more importantly, absolutely illegal. California families were already struggling with the high cost of housing before the pandemic, and these past two years have only made things worse.”

Attorneys for landlords said the attacks were unfair, and blamed the state for delays in reporting details about aid applications and complex new rules to file eviction papers. “This is so clearly politically motivated,” said Todd Rothbard, a landlord attorney in Santa Clara who received a letter on March 25.

The statewide eviction ban was enacted early in the pandemic to prevent tenants struggling with COVID-19 illness and job loss from becoming homeless. State lawmakers extended a narrow ban for the fourth time on Thursday, protecting renters who have aid applications under review by the state.

As many as 373,000 tenants have applications pending or are waiting for their landlords to get paid, according to an analysis of state data by the National Equity Atlas. State housing officials say the number is between 165,000 and 190,000 tenants.

The attorney general’s office received complaints that some landlords or their lawyers “may be falsely declaring that tenants have not notified them of a pending emergency rental assistance application in order to push through evictions,” Bonta said.

Landlords cannot remove a tenant for unpaid rent accrued during the pandemic unless a tenant has been denied assistance. The landlord can also evict if they have filed for relief and, after 20 days, have not received confirmation that the tenant has also filed an application.

Bay Area attorneys receiving the letters said they have no reason to file claims that can be disproved by data from the state’s Housing is Key website. Some have been asked to preserve files for a potential investigation.

Rothbard said delays in reporting applications and serving summons can create a gap between when a suit is filed and when a delinquent renter reaches out to the state.

Rothbard believes only three cases of the dozens filed by his office involved a tenant who had an active aid application. In one of those cases, the renter had texted the application to the landlord — but mistakenly sent it to an old phone number, he said. The case and two others were dismissed.

Daniel Bornstein, a landlord attorney in San Francisco, also received the letter and called it insulting and unfair. The state has made evictions more difficult during the pandemic, and attorneys shouldn’t be blamed for logistical errors. “When I first got it, I felt vulnerable,” Bornstein said. “Then, anger.”

Sid Lakireddy, Berkeley landlord and past president of the California Rental Housing Association, said property owners would rather keep people housed. “Evictions are very expensive to process,” he said. “It’s a last resort, not a first resort.”