California’s latest homebuying debacle is a pumped-up storyline we’ve seen before – even if each housing bubble has its own shape and size.

California housing has never been cheap and buyers must heavily rely on generous financing. And if the market looked bubbly – when values exceed economic logic – there’s usually an aggressive monetary benefactor helping to overinflate it.

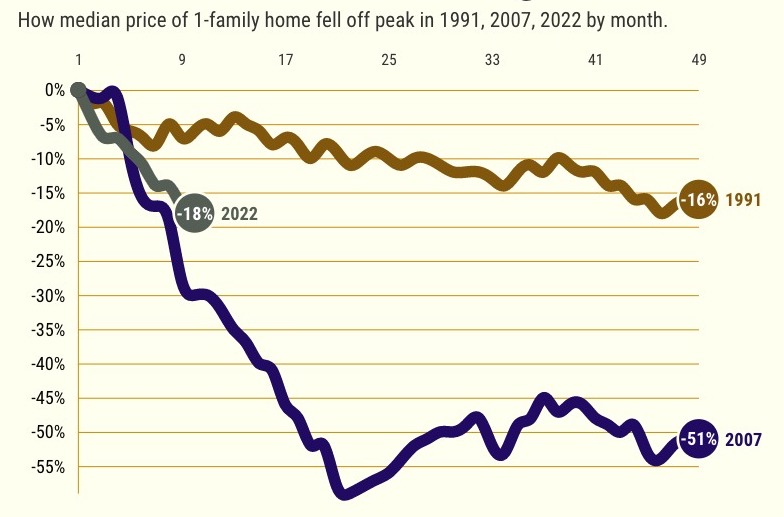

This tenuous relationship with mortgage money also creates volatility. When that monetary pump disappears, bubbles burst and the market takes an ugly reset.

The latest example comes courtesy of the Federal Reserve, which morphed from benefactor (the creator of historically cheap mortgages) to the villain (an economy-icing hiker of interest rates) in just two years.

The loss of that Fed pump chilled the pandemic era’s California homebuying binge. By November 2022, statewide home sales fell to their third-lowest level in Realtor data dating to 1990.

/*! This file is auto-generated */!function(c,l){“use strict”;var e=!1,o=!1;if(l.querySelector)if(c.addEventListener)e=!0;if(c.wp=c.wp||{},c.wp.receiveEmbedMessage);else if(c.wp.receiveEmbedMessage=function(e){var t=e.data;if(!t);else if(!(t.secret||t.message||t.value));else if(/[^a-zA-Z0-9]/.test(t.secret));else{for(var r,s,a,i=l.querySelectorAll(‘iframe[data-secret=”‘+t.secret+'”]’),n=l.querySelectorAll(‘blockquote[data-secret=”‘+t.secret+'”]’),o=0;o The median price of an existing, single-family home in California in February 2023 was $735,000, 18% off May 2022’s $900,000 high. That’s the third-biggest drop on record over these 10 months. This scenario is nothing new. Go back to the early 1990s, when the demise of mortgage-making savings and loans led to a slowly bursting California housing bubble. And who can forget the mid-2000s when the implosion of high-risk subprime lenders led to a rapid and sharp housing market crash? You see, California’s housing history has a bad habit of repeating itself. This bubble’s pop seemingly happened in slow motion. The statewide median price eventually fell 20% from its May 1991 peak. This era’s price pump was the savings and loan industry, a modern spin on the quaint financial institution that had a starring role in the holiday movie classic “It’s a Wonderful Life”. These mortgage specialists had essentially been bankrupted in the early by soaring interest rates of the early 1980s. S&L income from the old fixed-rate home loans they owned couldn’t cover the rapidly growing sums owed to depositors. So the government’s kick-the-can-down-the-road solution was to let S&Ls try to recoup their losses by making more bets. Many of those gambles were tied to real estate and helped fuel a 1980s housing boom in California. The S&L experiment flopped by 1989, eventually costing U.S. taxpayers more than $130 billion to insure the industry’s deposits. And California lost its housing pump. At the same time, the end of the Cold War meant the federal defense budget could be drastically cut. California’s large aerospace industry suffered as a result. That loss of middle-income generating jobs was another huge blow to the statewide economy and homebuying as well. It took almost eight years for the statewide median home price to reach a new high. Somebody had to be the new king of home financing. This bubble’s pump was the subprime lender, who made getting a mortgages far too easy. many of these firms were heavily financed by Wall Street brokerages that wanted to package mortgages and sell them as investments around the globe. These unorthodox loans – plus a resurgent California economy – combined for a feeding frenzy for housing. Prices surged 132% in six years. When too many of subprime borrowers failed to make house payments, however, their lenders failed, too. Foreclosures soared. Housing prices tanked. Mortgage bonds cratered. Unemployment skyrocketed. Banks teetered. A Wall Street giant, Lehman Bros., collapsed. And the Great Recession ensued. California home prices would plummet 59% from their May 2007 top. It took 11 years to recoup the losses. Oddly, the nation’s central bank that’s also a bank regulator was the pump for this bubble. As the pandemic throttled the nation’s economy in early 2020, the Fed did what it often does in dicey times: helped to prop up the business climate with lowered interest rates. However, the Fed gave housing an additional nudge by doubling its ownership of mortgage bonds to $2.8 trillion – as it clearly feared another housing crash. These actions pushed mortgage rates to a historic low of 2.6% by early 2021 – and the Fed kept rates below 3% for roughly a year. That stimulus, plus federal aid for the broad economy, was too much good stuff. Home prices, for example, jumped 53% in two years. Meanwhile, all this stimulus ballooned to inflation rates to highs not seen in four decades. You know, back in the early 1980s when the S&Ls sunk. This bubble’s pop came in early 2022 when the Fed’s pump ended. The central bank sharply reversed its interest rate policies hoping to chill an overheated economy. Mortgage rates swiftly doubled, icing homebuying. Oh, and a collection of banks collapsed – notably California’s Silicon Valley Bank – as their wrong-way bets on interest rates blew up. Bubbles are partly human nature, partly economic cycle. California’s housing market is prone to bubble conditions because of its dependence on bountiful financing required to keep its high-priced housing market in high gear. When lenders are generous or mortgage rates low, the housing market often thrives – and occasionally it gets too giddy. And when those pumps are turned off, prices dip and house hunting slows – and often swiftly. You know, the bubble pops. Jonathan Lansner is the business columnist for the Southern California News Group. He can be reached at jlansner@scng.com1990s: A wonderful life?

2000s: Too easy to get

2022: Too much good stuff

Bottom line