Startup exit tallies commonly underestimate biotech returns. Unlike most tech deals, the biggest profits in bio often come long after an IPO or acquisition.

Take Juno Therapeutics, a publicly traded cancer immunology company that sold to pharma giant Celgene this year for $9 billion. At first glance, it doesn’t seem like a deal that would impact Juno’s early investors.

After all, Juno went public back in 2014. Though the Seattle company raised more than $300 million as a private company, pre-IPO backers had years to cash out at healthy multiples.

Yet some held on. Bob Nelsen, managing director of ARCH Venture Partners, Juno’s largest VC backer, told Crunchbase News that his firm was still holding nearly its entire 15 percent pre-IPO stake when Celgene bought the company.

In the end, the acquisition netted ARCH’s limited partners 23 times their money, bringing in close to a billion dollars. It’s an exceptional return, even by venture home run standards.1

“We tend to distribute on milestones, not financing events,” Nelsen said of his firm’s approach to exiting a portfolio investment. That often means holding for years after an IPO awaiting positive clinical trial outcomes or other value-creating inflection points.

For public companies, that can be done over time or all at once, and usually comes in the form of company shares rather than cash.

So when is it an exit?

It’s outcomes like Juno that help explain why life sciences, despite bringing fewer first-day IPO pops and buzz-generating unicorn exits than the tech sector, still consistently attracts roughly a third of venture investment. Big exits do happen. But oftentimes it’s not with a lot of fanfare and usually not with a public market debut.

“I don’t think IPOs are ever an exit in biotech. It’s always a financing event,” Nelsen says. While ARCH may hold shares longer than the typical VC, he says it’s not uncommon to hang on the stakes for a while post-IPO.

That IPO-and-hold strategy appears to have worked out well for the firm on other occasions. Other portfolio companies that went public and were later acquired for multiple billions include Receptos, a drug developer, and Kythera Biopharmaceuticals, best known for an injectable to reduce chin fat.

Using Crunchbase data, we looked to see how common it is for a venture-backed biotech company to go public and then sell a few years later for multiple billions. We found at least eight examples of companies selling for $2 billion or more in the past five years that went public less than four years before the acquisition. (See list here.) Altogether, these acquisitions were valued at more than $47 billion.

Racking up post-IPO gains

It’s also not uncommon for biotech startups to grow into multi-billion dollar public companies a few years after IPO.

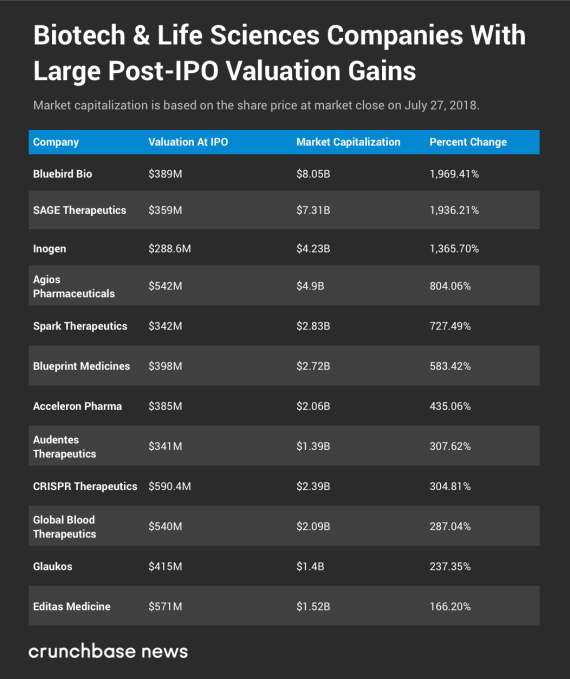

Using Crunchbase data, we put together a list of a dozen life science companies that went public in roughly the past five years and have recent market values ranging from $1.5 billion to nearly $9 billion. (This is a sampling, not a comprehensive data set, and was assembled based on exits of several top-tier life science VCs.)

On top was gene therapy juggernaut Bluebird Bio, which has seen a seven-fold rise in its stock price since going public five years ago. Next was Sage Therapeutics, a developer of therapies for central nervous system disorders, up more than six-fold since its IPO four years ago, reaching a market cap of nearly $8 billion.

Then on the device side there’s Inogen, a maker of portable oxygen concentrators for patients with respiratory ailments. It went public at a valuation of less than $300 million in 2014. Today it’s worth around $4.3 billion.

Yes, it’s true tech stocks can see massive gains a few years after going public, too. But the drivers are usually different. In tech, a company may see its stock jump after a big rise in sales, but it probably had sales in prior quarters. The business hasn’t fundamentally changed; it’s just improved.

Moreover, tech venture capitalists do generally consider an IPO an exit. While insiders usually can’t sell shares immediately, they’re typically comfortable liquidating when they can around the IPO price.

For bio, hitting key milestones changes the entire value proposition. A company can go from having no marketable product and no sales to quickly having one or both of those things.

Milestones and money

Returns from biotech startup M&A exits are also hard to pin down because of the widespread use of milestone payments. Buyers pay an upfront price with the agreement of more to come following favorable clinical trial results and a commercially successful therapy.

Often, it’s several multiples more to come if milestones are met. Take Impact Biomedicines, one of this year’s biggest private company exits. Celgene bought the company for $1.1 billion. However, the deal could be valued at up to $7 billion over time.

But the probability of hitting all the milestones seems low. To get the full $7 billion, global annual net sales of Impact’s therapies would have to exceed $5 billion. However, some milestones look more feasible, such as a $1.25 billion payment for obtaining regulatory approval.

This kind of deal structure is pretty common, and not just for M&A. A study by medical news site STAT analyzed nearly 700 biotech licensing deals and found that, on average, just 14 percent of the total announced value was paid out up front.

As with returns from post-IPO acquisitions, it’s hard to gauge just how well investors end up doing on these milestone-based purchases. The largest payoffs can be years down the road.

The opposite of tech

If it seems like the dynamics of a bio exit are, in many ways, the opposite of a tech exit, it’s worth considering how different the two sectors are at the early stages, too.

In the tech startup world, it’s common for a company to launch with an idea that sounds silly (tweeting, scooter sharing, air mattress rentals) and then suddenly be worth billions.

Bio companies are kind of the reverse. Practically every one sounds like a great idea (curing cancer, alleviating pain, treating neurodegenerative disease), and many turn out to be worth nothing. Investments that work out, however, may take a while, but eventually deliver in a big way.

- Making 23 times your money back is exceptional at all stages of investment. However, when it does happen, it’s most common at the seed stage for investment, where investors put in single digit millions or less. In the case of ARCH, 23X it is a particularly high return because it encompasses all the rounds Juno raised before going public.