By Ellen Nakashima | Washington Post

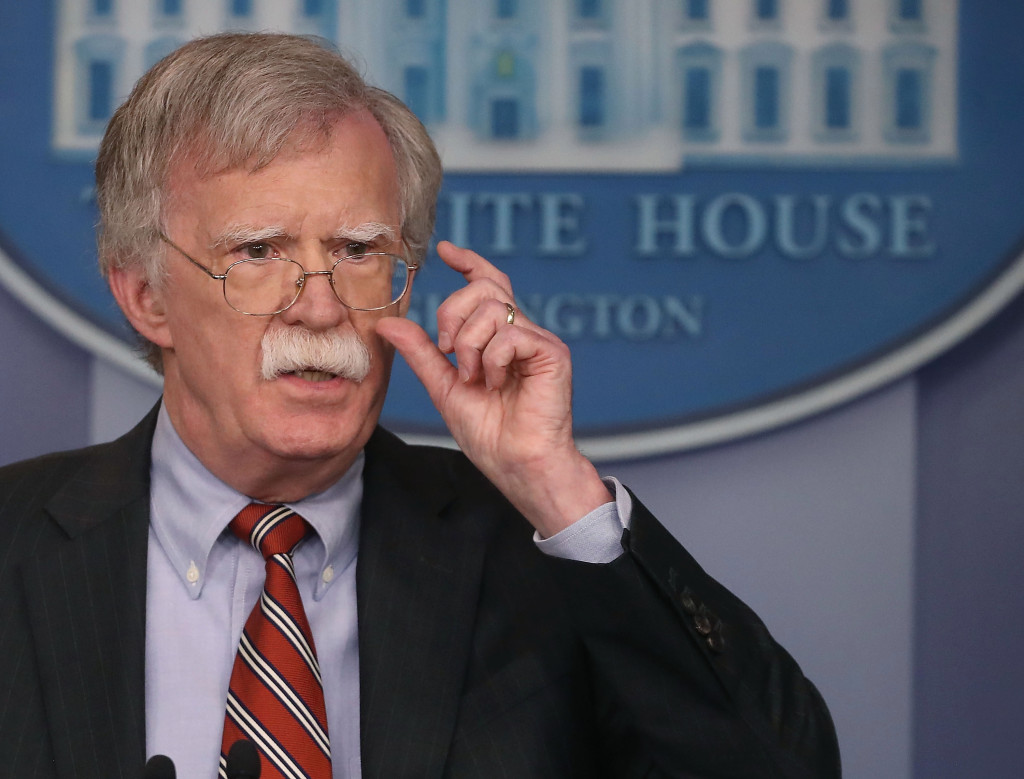

WASHINGTON — The White House has “authorized offensive cyber operations” against U.S. adversaries, in line with a new policy that eases the rules on the use of digital weapons to protect the nation, National Security Adviser John Bolton said Thursday.

“Our hands are not tied as they were in the Obama administration,” Bolton said during a news briefing to unveil a new national cyber strategy.

He did not elaborate on the nature of the offensive operations, how significant they were, or what specific malign behavior they were intended to counter. The Trump administration is focused on foreign governments’ attempts to target U.S. networks and potentially interfere in November’s election.

The strategy incorporates a new classified presidential directive that replaced one from the Obama administration, Bolton said. It allows the military and other agencies to undertake cyber operations intended to protect their systems and the nation’s critical networks.

Bolton’s remarks are consistent with the Trump administration’s more aggressive posture toward cyber deterrence compared with that of its predecessors. He cast the latest move as part of an effort to “create structures of deterrence that will demonstrate to adversaries that the cost of their engaging in operatings against us is higher than they want to bear.”

In general, the president’s directive — it’s called National Security Presidential Memorandum 13, or NSPM 13 — frees the military to engage, without a lengthy approval process, in actions that fall below the “use of force” or a level that would cause death, destruction or significant economic impacts, said individuals familiar with the policy who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss nonpublic information.

“As a policy matter, Bolton’s remarks likely mean they are willing to take more risks than previous administrations, but the proof will be in the results,” said Michael Daniel, Obama’s cyber coordinator.

Trump’s strategy builds off those put forward by previous administrations and incorporates initiatives already underway, such as using a “risk-management” approach to stanching vulnerabilities in critical networks.

Overall, they almost directly mirror the Obama administration’s national cybersecurity action plan issued in 2016, which grew from best practices developed by industry and the Commerce Department, said Ari Schwartz, a former senior cyber official in the Obama administration.

The strategy “does not go far enough in accelerating the reforms that need to be made,” said Rep. James Langevin, D-R.I., co-chair of the Congressional Cybersecurity Caucus. It’s good to clarify the roles of federal agencies in protecting critical infrastructure, he said. But “the document often fails to provide the strategic guidance regarding what trade-offs we should expect to make” between regulating and responding to the needs of critical system owners.

Langevin said it’s ironic that Bolton eliminated the position of White House cyber coordinator when he took office earlier this year — what he called “the very position best able to address these trade-offs at a national level.”

Bolton said he did so to “eliminate the duplication and overlap” on the National Security Council staff. He said that other directorates — intelligence and counterproliferation, for instance — were headed by directors, but did not also have a coordinator above that position.

The issue of responding to cyber provocations has been hotly debated for years. The Obama administration took criticism for being too slow and too timid. Some former officials pushed back, saying the obstacle to responding aggressively to a foreign cyberattack was not the policy, but the inability of agencies to deliver a forceful response.

“When you got to the point of saying, ‘OK, what do you have for us?’ there was not much ready to go,” said Schwartz, now managing director for cybersecurity services at Venable law firm.

The new White House document comes on the heels of a Pentagon cyber strategy issued this week that focuses on China and Russia as the United States’ top strategic adversaries. “This is attributed to their roles, respectively, in eroding U.S. military and economic vitality and challenging our democratic processes,” said Kate Charlet, a former senior Pentagon cyber official who is now at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

The Defense Department strategy also calls for “defending forward, confronting threats before they reach U.S. networks.” U.S. Cyber Command has always been tasked with defending the nation against attacks while operating outside U.S. borders. But now defensive activity will take place in the context of “day-to-day great power competition” rather than in crisis.

“The new approach derives from a growing consensus that lower-level malicious campaigns pose a major, cumulative risk and must be contested,” Charlet said. This is right, she said, but the Pentagon “must not find itself so focused on the day-to-day that it underprepares for major conflict.”

The strategy also makes more explicit the Defense Department’s role in deterring or defeating cyber operations targeting U.S. critical infrastructure that is “likely to cause a significant cyber incident.”