They all started with the best of intentions. Formation 8 talked about bringing “smart enterprise” to the corporate world. Social Capital talked about how to “fix capitalism” and Binary Capital wanted to “affect global behaviour change.” Rothenberg Ventures set out to “work on the biggest problems that change the world.”

Young founding partners debuting change-the-world funds were irresistible for chroniclers of the venture world, who too often had been forced to chat with balding and aging managing directors while hitting the links at resplendent country clubs. Everything was going to change in the venture world, and here was a new guard of progressive-thinking talent that would transform Silicon Valley forever.

Then it all came crashing down.

Social Capital fired nearly its entire remaining staff last week after seeing a mass staff exodus over the past few months. Formation 8 suffered deep acrimony between its founding partners, and its successive funds continue to deal with new challenges, such as a new, unreported lawsuit in California. Binary faced the Caldbeck sexual harassment situation, while Rothenberg imploded with allegations of financial fraud and mismanagement.

Some of the tales are sordid, while others are clearly the result of inexperience and hubris. But together, they weave a narrative for us that shouldn’t surprise anyone: giving hundreds of millions of dollars to neophytes wasn’t perhaps the best plan to build long-lasting funds.

The lessons though are myriad and broad. For founders, receiving investments from same-age peers may have made board meetings more relaxing, but at the cost of experience and oversight. Journalists who sat by while VCs built founding fables about themselves should have done more to pierce these reality distortion fields.

But perhaps most of all, the lessons need to be learned by limited partners. As LPs continue to lower their guard and drop due diligence in the race to get into the next hot fund, perhaps the combination of these stories can serve as a warning against rushing to write a check and being thoughtful about who to partner with in business.

The Valley finds its glamour

Sand Hill Road was the epicenter of venture capital. Its monopoly is increasingly being lost to downtown Palo Alto and SF. (Photo by Steven Damron used under Creative Commons).

It’s almost impossible to imagine today, but venture and the broader startup ecosystem used to be decidedly uncool. In the early 2000s, before the rise of blogs like TechCrunch and the breathless coverage of thousands of tech startups, Silicon Valley startups worked in the relative obscurity of the South Bay — the actual Silicon Valley of lore. A boring suburban hell of sorts, startups attracted the misfits and the communalists, and most definitely the engineers who saw in the internet the future of human society.

Things changed as the global financial crisis struck in 2008. The startup world began to migrate north, to San Francisco. Technology went from a backwater industry to the forefront of global power and commerce. Once the bastion of nerds, the MBAs and other pretty people started pouring in, ready to seek out fortune — the tech that might drive it be damned.

Perhaps most importantly, glamour hit the tech world hard. Conferences like Disrupt and AllThingsD propelled formerly unknown entrepreneurs to the heights of fame. Exec comms became de rigueur for founders, and venture firms equipped themselves with some of the best communications talent they could find.

Yet, while the entrepreneurs were increasingly speaking about “saving the world,” the venture firms were not. Stodgy, venerable and just plain old (and white and male), the stalwarts of Sand Hill Road (the epitome of a suburban hell street complete with a full-service gas station) struggled to adapt their boring Excel number crunching thinking to this new world.

Their firms — and LPs — noticed, and responded by trying to hire a new crop of partners, operators with the cachet to win over founders and snare the next great deal. Operators had very different mentalities from traditional venture folks, but that was okay in the competition for the next hot startup.

But as any Silicon Valley enthusiast knows, the path to disruption doesn’t lie through evolving incumbents. Instead, it’s about founding startups, or in this case, new venture firms with fresh perspectives that connect with founders looking for a friend on their board rather than competent but mature directors who were older than their grandparents.

The best-laid plans of mice and VCs…

Joe Lonsdale of 8VC. David Paul Morris/Bloomberg via Getty Images

And so we get Joe Lonsdale, a co-founder of Palantir, who left and eventually started Formation 8 at age 30 with Brian Koo, age 33, scion of the Koo family of South Korea, which owns the LG conglomerate, along with long-time VC investor Jim Kim. They raised $448 million for their first fund in 2013, the largest debut in the history of venture. Lonsdale described the firm’s investing style simply: “First and foremost, we invest in driven entrepreneurs who we believe will change the world.”

We get Jonathan Teo, aged 34, and Justin Caldbeck, aged 37 (and the oldest of the pack!), two young but reasonably experienced venture capitalists peeling off of their venerable funds (General Catalyst for Teo and Lightspeed and Bain for Caldbeck) to start Binary Capital, which began with a debut fund of $125 million in 2014 and raised another $175 million just two years later. Teo, speaking to a Singaporean magazine, explained that “We are at the centre of the tech ecosystem, and consumer technology is the highest leverage a company has to affect global behaviour change.”

(That same article noted in its intro that “It is not every day that someone buys a Boeing 747 as a gift. But that was exactly what Jonathan Teo did last year, when he gathered a group of Silicon Valley tech titans to purchase a used plane and donated it to Burning Man, an annual experimental art festival held in Black Rock Desert, Nevada.” Burning Man may well be one of the most inter-connected events for all of these folks).

Justin Caldbeck, formerly of Binary Capital. Michael Short/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Chamath Palihapitiya, who spent four years at Facebook early in that company’s history and eventually headed growth, would start Social+Capital Partnership in 2011 and synced up with experienced hands Ted Maidenberg and Mamoon Hamid. Palihapitiya, aged 34 and a self-described “Merchant of Progress,” said that he wanted to “fix capitalism.” In an interview with Fast Company’s Ainsley Harris, he said, “But you can fix capitalism. And the reason you can fix capitalism: It is inherently numerical, and as a result, it is inherently objective. It can be done objectively.”

Rothenberg may not have raised the same kind of moolah, debuting with a $5 million seed fund in 2013, but Rothenberg spread his wings far and wide in San Francisco, opening up his apartment and co-working facilities to create a community of entrepreneurs. He loved the press and media attention and outlandish behavior, eventually hosting a now infamous field day at the SF Giants baseball park in SoMa. As he explained during an interview at Stanford, “…we can build and create awesome experiences, people care about that and then we can actually work on the biggest problems that change the world and that’s awesome…”

These four firms flouted venture conventions, and sought out the path-breaking investments that would drive returns. Formation 8 struck a bit of gold with its exit of Oculus to Facebook and RelateIQ to Salesforce. The rebranded Social Capital bought into high-flying startup Slack, and also led the Series A into Intercom. Binary invested in young consumer startups like Bellhops and Shoptiques and Havenly according to PitchBook. Rothenberg invested heavily in VR and also in popular companies like Boosted, Apartment List and Chubbies, albeit with mostly tiny checks.

These firms were designed to cultivate the next generation of founders, and on that front, they succeeded. If only that was the sole benchmark for success.

… often go awry

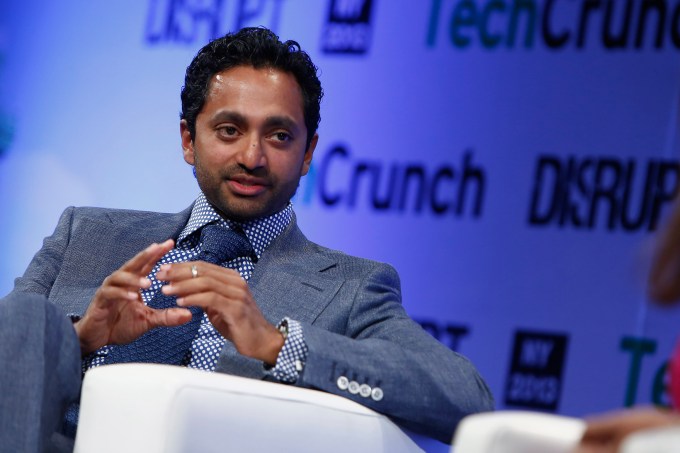

Chamath Palihapitiya of Social Capital. (Photo by Brian Ach/Getty Images for TechCrunch)

Tolstoy begins Anna Karenina with the line that “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

The same is true of venture firms. Portfolio returns can easily make everyone happy, but when firms blow up, they all blow up in their own, idiosyncratic ways.

Formation 8 was the first of the set to disintegrate. Part of the equation was accusations and a lawsuit against Joe Lonsdale around a sexual assault — allegations that were in the end dismissed. But the challenges internally at the firm far pre-dated those challenges. As William Alden at BuzzFeed chronicled at extreme length, Lonsdale and Brian Koo were at loggerheads over investment strategy, and even the geography of where the Formation 8 offices should be located in the Bay Area. Plus, they had a fight over a Korean restaurant Koo tried to open in Palo Alto. There were also the lurid details of the Hyperloop One imbroglio, where Lonsdale was a board member.

The two ended up separating, with Lonsdale creating 8VC and debuting with a $425 million fund and Koo starting Formation Group with a $357 million fund.

Yet, the troubles continue. A lawsuit — so far unreported — was filed in the United States District Court for Northern California this past June, alleging that Koo and Formation Group and its affiliates committed “fraud, breach of contract, breach of the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing…“ by failing to pay a partner named Martin Robinson and a principal named Selvam Moorthy. That litigation remains ongoing according to district court records, where the parties are due to discuss a motion to move the matter to arbitration.

Lonsdale, for his part, has certainly shied away from the media, and has been in a rebuilding phase, eventually nailing a second fund for 8VC of $640 million earlier this year.

Partner fallout is one version of an unhappy venture firm, but Binary Capital disintegrated due to alleged sexual harassment by Justin Caldbeck from multiple women in Silicon Valley. He would eventually come to be the Silicon Valley poster boy for the MeToo movement, and was sued by a former employee of Binary. The firm’s assets were sold to LHV earlier this year, and it is now essentially a non-entity.

Rothenberg Ventures team

Meanwhile, Rothenberg has been facing tougher challenges. He faced a litany of investigations over his fiduciary responsibilities to his fund, eventually being charged by the SEC last month for fraud. That criminal trial is ongoing.

And then we get to Social Capital, whose troubles appear to be more managerial. Palihapitiya’s two early partners, Maidenberg and Hamid, both decamped to other firms. There has now been a complete exodus of partners and staff at the firm, with even more layoffs taking place just in the last few days. The fund is no longer raising outside capital.

Outside of Palihapitiya, the math on who is left remains decidedly unclear. The Information quotes Palihapitiya as saying that “I would rather spend time with the people that are 100% aligned with what I want to do and the person that’s most aligned with what I want to do is me.”

That shouldn’t be a problem when there is no one else in the room.

Lessons for founders, VCs and LPs

RubberBall Productions via Getty Images

Silicon Valley loves a great story. We love the entrepreneurs who fight like hell to build their companies, who beat the odds against incumbents and competitors. We love the drama of business, of Uber against Lyft and Airbnb against city governments. We want the underdogs to win.

At some point though, we need to evaluate our own narrative fetishes. We need to see through the loud pronouncements, the ambitious quotes, the glossy marketing. Especially in venture capital, where excuses for poor performance are a common trade, we need to resurrect the age-old skill of simply looking at the numbers and evaluating quality. As my VC mentors over the years have consistently said: VC is not an investment business, it is a returns business.

We also need to reevaluate our patience. Startups take 12 years or more to build and exit, but VC firms have a much longer cycle. They are meant to last, because they owe broad obligations to so many other firms through the board seats they hold.

Partner turnover is up at many firms, despite the damage that does to startup governance. Even worse is when a firm disintegrates entirely. We should celebrate the slow and steady on the finance side, and leave the quick growth to the startups.

In a region that reveres the young, we also need to remember that many jobs are ultimately dependent on experience, and venture capital is certainly one of them. VC is its own trade, with learnings and techniques that build up over a lifetime of investing. That doesn’t mean that young people have nothing to offer — far from it. But it does mean that our indexing should not just assume that a 30-something automatically has the capacity to manage a complex front and back office team and invest hundreds of millions of dollars in a few short months.

LPs face the greatest challenges in this area. They are the guardians of their funds, since after all, it’s their money that will be lost. But the timing to get into a hot investor’s hand can be extraordinarily limited, and even asking a question or two could lead them to be cut out of a fund’s subscriptions. LPs need to band together and refuse to concede to these demands. Due diligence doesn’t have to be exhaustive on a debut fund, but it should also not be de minimis. Some coordination here is just absolutely needed to ensure a basic level of integrity.

It’s said that new VCs need to down an F-16 in order to learn the trade. Together, Formation 8 raised $1.39 billion, Social Capital $1.3 billion, Binary $300 million and Rothenberg $70 million, according to PitchBook.

That’s a $3 billion education for these partners, and for all of us.