Airware desperately sought cash for 18 months before running out of money and shutting down last month, leaving about 120 employees without jobs after the startup had burned $118 million in funding. Bandaid strategic investments from construction company Caterpillar and others kept Airware alive as it looked for a $15 million round, according to a former employee.

A late pivot from hardware to drone software sales through Caterpillar’s dealers went sour, as Airware lacked the features found in competitors and suffered from slow engineering cycles. “So Caterpillar told them, ‘We’re not going to fund you any more. We’re pulling our money.’ So Airware didn’t make payroll,” the source says. The sudden shutdown of one of the most-funded drone startups sent a shock wave through the industry.

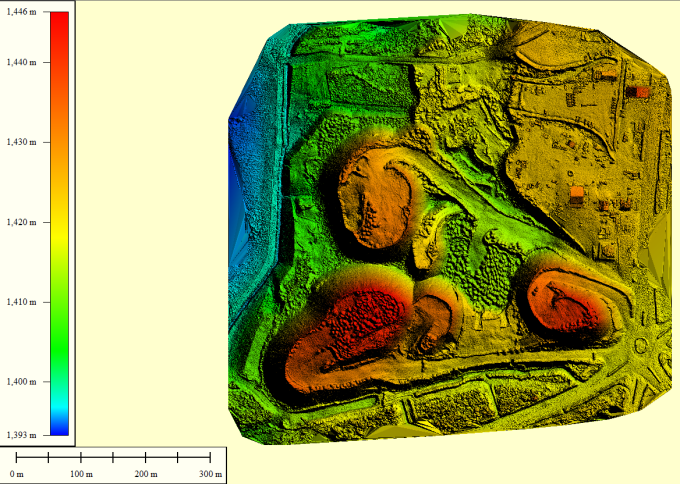

Luckily, at least part of Airware’s team is being rescued from the wreckage. French drone services company Delair is buying Airware’s Redbird analytics software and IP, plus the 26 employees who ran it. Airware had acquired Redbird and its 38-member team in 2016 to integrate its analytics that derived business metrics from 2D maps and 3D models of work sites based on imagery shot by drones.

Now the Redbird team will do that for Delair, bringing along its relationships with 30 drone dealers and 200 customers to try to make sense of aerial imagery from construction sites, mines, energy infrastructure and more. “We managed to keep that business alive with Delair,” says Redbird CEO Emmanuel de Maistre. “Customers wanted us to keep this going. They were very worried to not have a solution anymore.” He says that Airware still isn’t formally in bankruptcy or administration, and that as it’s been “actively reaching out to players in the market, to sell the assets . . . Interest from software companies and hardware companies was quite high.”

Founded in 2011, Delair now has 180 employees selling its UX11 mapping drone, data processing software and enterprise integration services to get businesses properly equipped with unmanned aerial vehicles. Delair had previously raised $28.5 million, and last month added a strategic Series B of undisclosed size from Intel — also an Airware investor. Delair co-founder Benjamin Benharrosh tells me that while his company started in hardware and bought Trimble’s UAV business Gatewing in 2016, “lots of the growth now is dedicated to the software,” so the Redbird buy makes sense.

Meanwhile, Airware’s hardware assets are going to auction on Wednesday. Heritage Global Partners will be selling dozens of DJI drones plus networking equipment and computers. Terms of the Delair deal weren’t disclosed, but the money from that sale and the auction could help Airware pay off any outstanding debts or commitments. However, Airware’s A-List investors, including Y Combinator, Google’s GV, Andreessen Horowitz, First Round, Shasta, Felicis, Kleiner Perkins and Intel, aren’t likely to recoup much of their capital. We’ve reached out to Airware, its founding CEO Jonathan Downey and its final CEO Yvonne Wassenaar for comment and will update if we hear back.

Founded in 2011, Airware tried to build a drone operating system before moving to sell drone hardware to commercial enterprises. But the rapid ascent of Chinese drone maker DJI pushed Airware to pivot out of hardware sales and toward drone data collection and analysis services. But a source says that since the startup entered this market late after the hardware boondoggle, “Airware’s technology was pretty far behind. They didn’t have a lot of the feature set a lot of others in the space did, like Propeller, 3DR and DroneDeploy.” Airware lacked seamless data uploads and quick processing times.

“What happened in the company wasn’t so much that the management team didn’t manage it correctly. The sales team just couldn’t sell a product that didn’t work as easily as it needed to compared to other products in the market,” our source says. They noted that Wassenaar, who’d replaced Downey as CEO in June 2017, had done a good job and been dedicated to fundraising to save the company since she joined. “Ultimately it was a matter of bad timing, and they didn’t have the engineering to overcome bad timing,” our source says. “The issue Airware had was a lack of funding. They ran out of runway,” confirms Redbird’s de Maistre.

Airware’s story should serve as a warning to startups raising at high-flying valuations. If a pivot doesn’t go smoothly or new competitors emerge, investors may disappear rather than back a down-round that might save the company but leave it in a downward spiral. Once a startup loses momentum, even having top investors and a ripe potential market can’t always stop it from disappearing into the sunset.