As an engineer and Stanford PhD candidate in science education, I often travel to the Galapagos Islands to work with teachers. Leaving from the San Francisco airport, I start to get worried the minute I walk up to TSA. Why? As an Afro-Latina, with a fluffy and kinky ‘fro, I will, once again, be designated for special screening.

Last time, a TSA officer violated my hair, inserting their fingers in a frantic but unsuccessful search for explosives. I ended up missing that flight, but I don’t even blame the TSA agent. The real perpetrators were the machines and algorithms used to identify dangers. I have an Afro. Therefore, I am a threat.

Technology discriminates against minorities and women because its creators are rarely part of these populations. In the United States, the fields of engineering and technology have a huge diversity problem. The 2018 Census data shows that more than half of the population identifies as minority and women. Yet, these populations make up less than 15% of the engineers who design technologies. Their inclusion is an issue of social justice and an economic imperative.

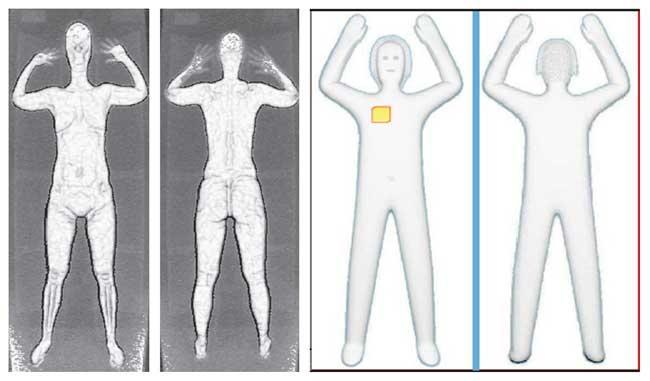

Let’s go back to the airport scanners. Although full-body scanners speed up the process at airports, they discriminate against women of color. These scanners are prone to false alarms toward hairstyles popular among black people, such as Afros and braids. To develop technologies that are sensitive to racial and gender issues, we need engineers who understand the struggles of women and people of color and possess membership in these groups. Yet, companies focus on building products without considering ethical issues beyond privacy. Organizations are rarely looking at who is designing solutions.

The algorithms that customize our everyday experiences have expanded rapidly, with similar biases as the scanners. These computer models, used by social media platforms, offer products based on race and gender. Facebook recently faced discrimination charges based on limiting housing advertising on the basis of race. Social media manipulation of information makes minority groups, who already face discriminatory practices, even more vulnerable, as shown by professors at Georgetown University.

For example, research at Carnegie Mellon University examined discriminatory practices in hiring via online social networks. The researchers focused their study on information that it is not traditionally communicated through resumes. Among employers who searched candidates in social networks, candidates from minority groups received 15% fewer calls. Even though the resumes were blind to race and gender, online networks make an applicant’s information visible.

Discriminatory practices in technology are pervasive. Technologies are hurting those who don’t look or speak like their creators.

In the near future, with the advent of Augmented Reality Cloud, companies are developing virtual worlds that exist on top of the real one we live in. Soon, you will be able to look at a person and have instant access to all available information about them.

In this brave new world, our personal information will be in the hands of the very few who dominate the tech culture. The creators of this world hold an unimaginable power. By no means are these creators bad people, but as everyone else they hold implicit biases. If you think that airport scanners and social media discrimination were scary, imagine a whole world in which our more intimate details exposed.

Technological progress is inevitable. Many of these advancements may benefit some but can also hurt many others. If we want technology to benefit all of us, we need to integrate diverse voices into the tech industry. Until then, technology will continue to discriminate against more than half of our population. And, I will miss more flights.

Greses Pérez is an engineer and educator pursuing a PhD at Stanford University in science education and Learning Sciences and Technology Design.