Hello and welcome back to our regular morning look at private companies, public markets and the gray space in between.

It’s the second to last day of 2019, meaning we’re very nearly out of time this year; our space for repretrospection is quickly coming to a close. Before we do run out of hours, however, I wanted to peek at some data that former Kleiner Perkins investor and Packagd founder Eric Feng recently compiled.

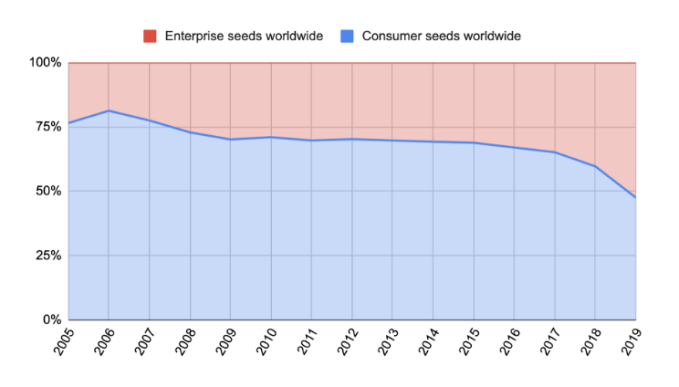

Feng dug into the changing ratio between enterprise-focused Seed deals and consumer-oriented Seed investments over the past decade or so, including 2019. The consumer-enterprise split, a loose divide that cleaves the startup world into two somewhat-neat buckets, has flipped. Feng’s data details a change in the majority, with startups selling to other companies raising more Seed deals than upstarts trying to build a customer base amongst folks like ourselves in 2019.

The change matters. As we continue to explore new unicorn creation (quick) and the pace of unicorn exits (comparatively slow), it’s also worth keeping an eye on the other end of the startup lifecycle. After all, what happens with Seed deals today will turn into changes to the unicorn market in years to come.

Let’s peek at a key chart from Feng, talk about Seed deal volume more generally, and close by positing a few reasons (only one of which is Snap’s IPO) as to why the market has changed as much as it has for the earliest stage of startup investing.

Changes

Feng’s piece, which you can read here, tracks the investment patterns of startup accelerator Y Combinator against its market. We care more about total deal volume, but I can’t recommend the dataset enough if you have the time.

Concerning the universe of Seed deals, here’s Feng’s key chart:

Chart via Eric Feng / Medium

As you can see, the chart shows that in the pre-2008 era, Seed deals were amply skewed towards consumer-focused Seed investments. A new normal was found after the 2008 crisis, with just a smidge under 75% of Seed deals focused on selling to the masses for nearly a decade.

In 2016, however, a new trend emerged: a gradual decline in consumer Seed deals and a shift towards enterprise investments.

This became more pronounced in 2017, sharper in 2018, and by 2019 fewer than half of Seed deals focused on consumers. Now, more than half are targeting other companies as their future customer base. (Y Combinator, as Feng notes, got there first, making a majority of investments into enterprise startups since 2010, with just a few outlying classes.)

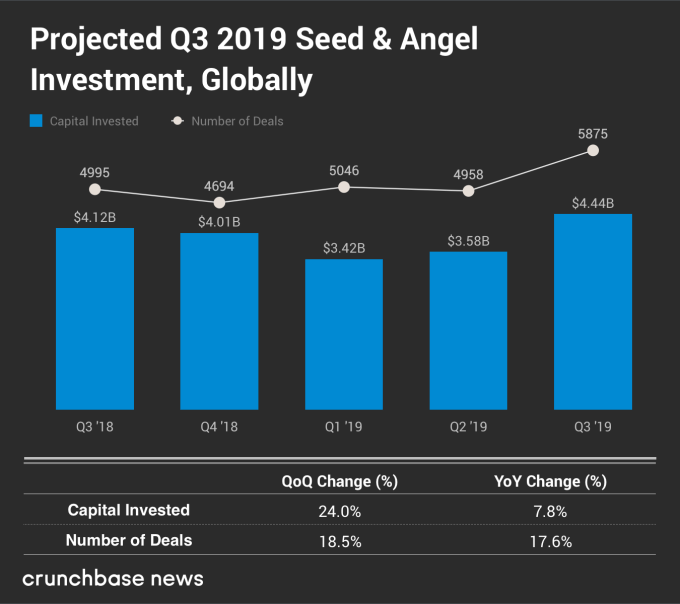

This flip comes as Seed deals sit at the 5,000-per-quarter mark. As Crunchbase News published as Q3 2019 ended, global Seed volume is strong:

So, we’re seeing a healthy number of deals as the consumer-enterprise ratio changes. This means that the change to more enterprise deals as a portion of all Seed investments isn’t predicated on their number holding steady while Seed deals dried up. Instead, enterprise deals are taking a rising share while volume appears healthy.

Now we get to the fun stuff; why is this happening?

Blame SaaS

As with many trends long in the making, there is no single reason why Seed investors have changed up their investing patterns. Instead, there are likely a myriad that added up to the eventual change. I’m going to ping a number of Seed investors this week to get some more input for us to chew on, but there are some obvious candidates that we can discuss today.

In no particular order, here are a few:

- Snap’s IPO: Snap went public in early 2017 at $17 per share. Its equity quickly spiked to into the high 20s. By July of that same year, Snap slipped under its IPO price. Its high-growth, high-spend model was under attack by both high costs and slim gross margins. Snap then went into a multi-year purgatory before returning to form — somewhat — in 2019. It’s not great for a category’s investment pace if one of its most prominent companies stumble very publicly, especially for Seed investors who make the riskiest bets in venture.