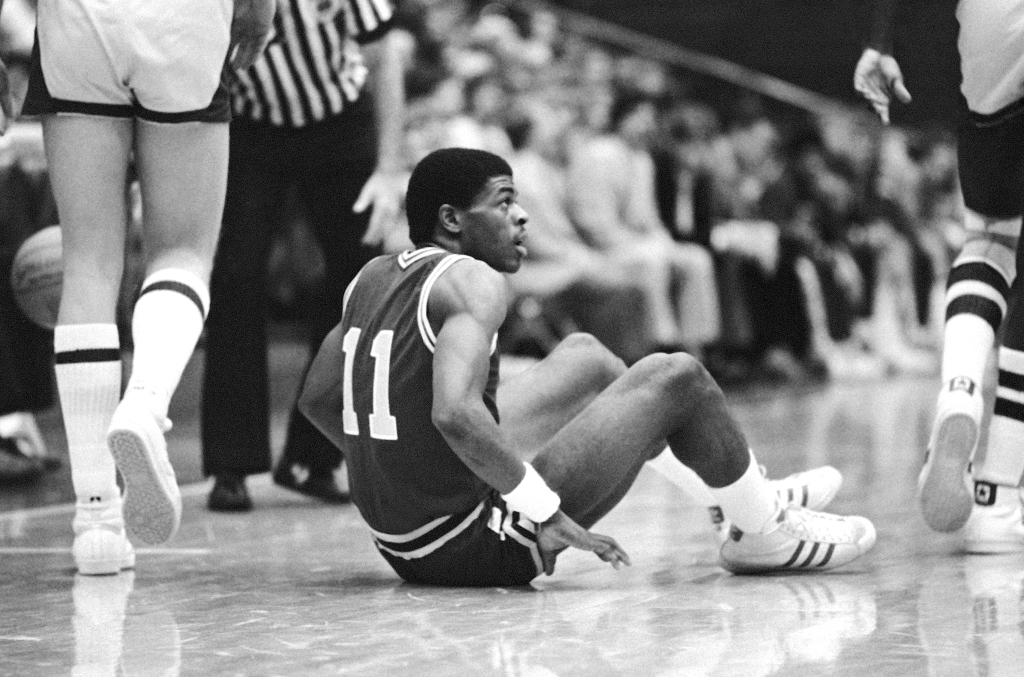

Dwight Anderson was a flesh-and-blood video game. He averaged 38 points at Roth High in Dayton, Ohio, and his games became too big for the gym. Isiah Thomas called him “Michael Jordan before Michael Jordan.”

But when Anderson sought quiet time, he played Pong, the amazing breakthrough of the late 70s, a leisurely antique today. Like Anderson, it was an original.

“Dwight had a tutor whom he loved,” said Stan Morrison, the USC coach at the time. “If he did what he was supposed to do, she’d let him play Pong. We had our Senior Night, and it was too expensive for his parents to fly out. So Dwight invited this lady to escort him onto the court. It was touching. His teammates knew the back story.”

The front story was self-explanatory. In the waning days of vinyl, Anderson played at 78 rpm.

He exceeded the dimension of the court one night in 1982, when he ran down a wild pass at the Sports Arena, and barged past the end line. Before he landed, he turned and flipped it over the backboard and through the hoop.

Such plays are illegal today. Morrison had to call time out because his bench was so out of control. USC beat Washington and won the Pac-10.

Anderson began at Kentucky, where play-by-play man Cawood Ledford dubbed him “The Blur.” The trouble came when the game was unplugged. Cocaine provided its own blur, and Anderson couldn’t outrun it.

His problem was no secret, and he fell to the second round of the draft, and played five NBA games before he spiraled to the Continental Basketball Association and then the Phillippines.

Anderson returned to Dayton and was badly beaten, losing his teeth. He lived in a crawlspace at his parents’ house, or sometimes slept on the front porch, in the cold. According to Tom Archdeacon of the Dayton Daily News, Anderson talked of selling all his trophies for drug money. But he also got a job at McDonald’s and showed up at Indiana Pacers’ camp. He made it to the final cut.

Finally Sedric Toney, a former U. of Dayton star, and other friends got Anderson to John Lucas’ rehab center in Houston, where Dirk Minnifield, an ex-teammate at Kentucky, greeted him.

Anderson reassembled his life and was working in a linen factory, still clean, when he died last week, at 61.

“He had more speed, jumping ability and body control than anyone I’d ever seen,’ said Clayton Olivier, a USC teammate, now a girls’ coach at Mater Dei. “But I remember that smile he always had on his face. He had a Dodge with some big speakers in it, and he loved his music.

“He loved being with his teammates but he loved the night life, too. We always tried to keep him away from the bad people.”

Cocaine should have been on basketball’s warning label back then. Len Bias, Roy Tarpley, Chris Washburn, John Drew, Lamar Odom, Richard Dumas, Micheal Ray Richardson, Shawn Kemp and Lucas himself either lost their lives or their careers or both.

Their successors either learned from them or found smarter examples. Jordan, Magic Johnson and Larry Bird were too busy for self-destruction. Vegan chefs have replaced drug dealers in the new, righteous NBA world.

The man who loved Pong was born too early.

This was a magic time in college basketball, and Anderson had won the MVP award in a prep tournament that included Thomas, Ralph Sampson, James Worthy and Dominique Wilkins.

At Kentucky, the freshman keyed a comeback from six down with 30 seconds left to beat Kansas. He scored 17 points in 19 minutes to upset Notre Dame. But, mysteriously, Anderson transferred, back when transferring was more of a betrayal than a strategy.

“He had been experimenting with coke in Kentucky but you don’t really experiment with coke,” said Branson Wright, a documentarian whose film on Anderson is “The Blur.”

“Going to L.A. put him over the edge. I really think if he’d stayed, he wouldn’t have had those problems.”

In recent years Anderson played in a 40-to-50-year-old league and still had the touch. He and Wright showed the film to youth groups.

“One day the kids were rowdy and the teacher had to stop the film twice to get them calmed down,” Wright said. “Dwight came out and cussed them out and said, ‘I didn’t get addicted to drugs and become homeless to listen to that.’ When he was done, the kids were lining up for selfies.”

The line to meet Dwight Anderson should have stretched deep into the 90s and the next century. As he learned and as we all should, life is the Blur.