The Federal Reserve, which raised its benchmark interest rate last week, essentially plays the role of party pooper with two conflicting chores — keep inflation low and employment high.

Conflict arises when one of those key economic forces gets out of whack. Why? Because the Fed’s favorite way to fix either poorly performing sector is to put one of them at risk.

So, as the nation’s central bank begins another attempt at this high-wire balancing act, let’s ponder whether its fight to tame inflation will cost you a job.

When the party’s over

Here’s the problem: Inflation is running at a 40-year high. The central bank on May 4 took a massive swing at this challenge with its most powerful tool — the interest rates it controls.

The target for the benchmark Fed Funds rate was upped this week by a half-percentage point, the largest hike in 22 years. And Fed Chairman Jerome Powell was quite clear — there will be more hikes, likely this summer.

Remember, the Fed is like a bartender and we’re now well past “last call!”

Central bankers know how to start a party. Their favors — cheaper financing — can be a great propellent to business activity. Historically cheap rates in this pandemic era have played a big part in the current inflation mess.

At the same time, the Fed’s also empowered to use expensive financing to end the festivities when the party gets out of control. Like 2022.

But will this edition of Fed-style temperance work? What are the consequences? And how quickly will we see the results?

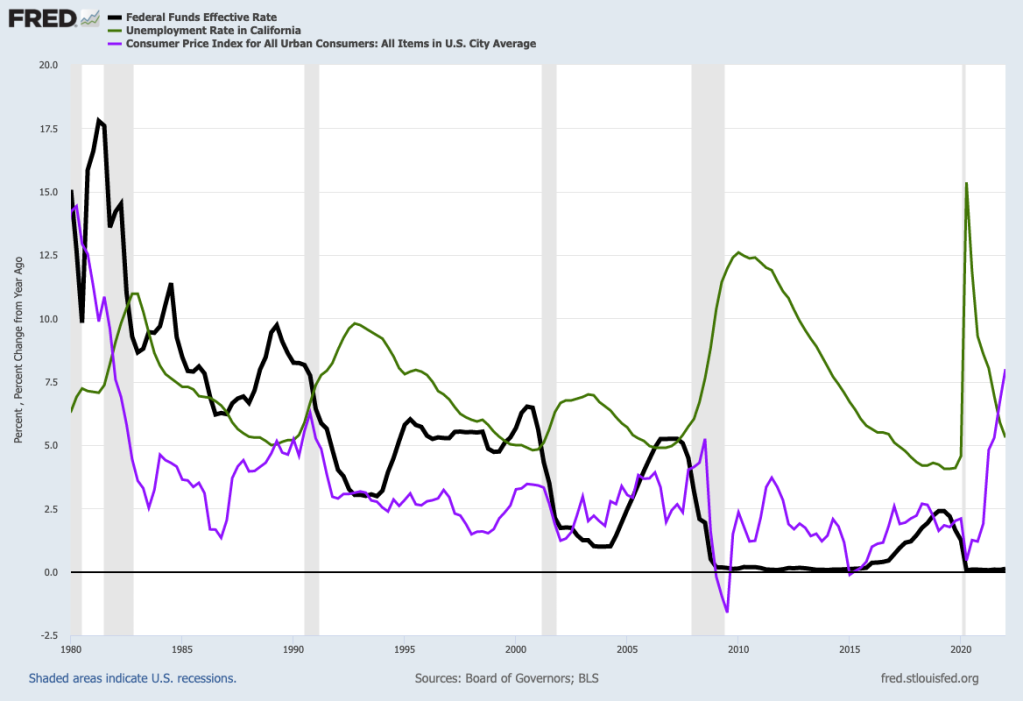

My trusty spreadsheet used several key economic yardsticks to score the Fed’s track record, pulling four decades of data from the Fed Funds rate (St. Louis Fed), the U.S. Consumer Prices Index (Bureau of Labor Statistics), California unemployment (BLS), U.S. gross domestic product (Bureau of Economic Analysis) and California home prices (FHFA index).

The quest: What happens in the three years following the largest quarterly increases in the Fed Funds rate? For those too young, or with poor memories, in those crazy inflation days of the early 1980s, the Fed made a bold move — creating a recession with double-digit interest rates that iced rising prices.

My spreadsheet’s review says the Fed’s actions typically cool inflation, eventually. Economies take time to adjust to business-throttling jumps in financing costs. But those adjustments also explain why these Fed actions crimp economic growth and lead to increased unemployment.

Since 1980, Fed Funds have risen in nearly half of all quarters. Let’s look at what history tells us what happened, on average, following the top 25% of all Fed Funds moves over four decades …

First 12 months

In the year following major rate increases, inflation cooled by an average 0.6 percentage points. That’s a significant cut for an economic benchmark that’s averaged 3.3% over four decades.

The broad impact was swift, too. Business output slowed. GDP growth cooled by an average 0.9 percentage points — a sharp dip for the economy, which has grown at 2.6% pace since 1980.

California’s impact was initially muted.

Unemployment only fell by a tiny 0.1 percentage point as economic momentum didn’t cool much. That helps explain why the statewide home price average rose 8%. Rising rates also often create a rush of buyers thinking it’s the “last chance” to buy.

Painful second year

The Fed’s rate wand again chilled inflation, with cost-of-living increases slowing by another half-percentage point in the second 12 months after major rate hikes.

Business output contracted again. GDP growth fell, too, by 0.2 points.

That widespread weakness is behind California’s unemployment rising 0.4 points. And, yes, home prices increased — but only by 2%. Pricier mortgages — and fewer jobs — stung.

Year three hurts, too

Yes, the Fed squeezed inflation again, chilling the CPI’s advance by another 0.6 percentage points.

However, GDP was essentially flat. California unemployment jumped another half-percentage point. And statewide homes prices rose a slim 1%.

3 years later

The Fed is pretty good at whipping inflation — 36 months after major rate jumps.

CPI growth was down in 76% of three-year periods since 1980. Inflation was 1.7 percentage points slower, a significant change for an economic marker that’s run at a 3.3% annual pace over four decades.

The collateral damage in this war on inflation was significant, too.

U.S. business output slows 65% of the time. GDP’s average three-year change was a growth rate 1.1 percentage points lower. Remember, GDP expansion has run 2.6% a year for four decades.

California unemployment was higher in just 57% of the three-year periods after big rate hikes. Yet the average result was a 0.8-point increase in joblessness, which has averaged 7.2% statewide since 1980.

And statewide home prices? There’s an 84% chance they’ll rise — but the average gain is a 4.4% annual increase is below an overall appreciation pace of 4.9% yearly since 1980. Yes, rising rates cool housing.

Bottom line

Why is an unelected board — the Fed — making this critical choice: inflation or jobs?

You don’t expect politicians, especially in this hyper-partisan era, to make significant decisions or create a reasonable fix, if legislation could even pass. Not a good scenario when rising inflation isn’t a problem that can be left to simmer too long.

It adds up to looking ahead to three years from now. If you’re still gainfully employed and inflation fears have evaporated, you might even cheer the Fed.

If you lost your job amid the inflation fight, you’ll think the Fed stinks.

Postscript

Have you heard all the Wall Street chatter about higher rates hurting the stock market?

Well, this same math shows that three years after big rate hikes, there was an 81% chance stocks rose — and the average gain was 14% a year vs. an 11% annual rate of increases since 1980.

I hate to be jaded, but less inflation and fewer workers can boost many corporations’ bottom lines.

Jonathan Lansner is business columnist for the Southern California News Group. He can be reached at jlansner@scng.com